The Sunfaced Trees of Ogma

“Where do the images and names expressed by the letters B, L and N come from? They come from the twigs and branches of the oak. The branches suggested the thoughts which they expressed in sound. From the tree’s trunk, its noblest part gave rise to the seven principal characters — the seven vowels: A, O; U, E, I, EA, OL. Later three others were formed, added to supplement the first seven. UI, IA, AE… The branches of the tree serve as the model for all twigs and offshoots of the Ogham line, which governs them all. The tribe B, descended from the birch and its ‘son,’ the ash, is the principal tribe; from it the first alphabet arose; I — from Auis, the mountain-ash; F — from Fearn, the alder fit for shields; S — from Saille, the silvery willow; N — from Nin, the ash fit for spears; H — from Huat, the hawthorn, a treacherous thorny bush; D — from Duir, the noble oak; T — from Tinne, holly or possibly elder; C — from Coll, the hazel; Q — from Quert, the apple, or perhaps aspen or rowan; M — from Mediu, the graceful vine; Q — from Quert, the ivy; NG — from Ngetal or Gilcach, the reed; ST or Z — from Draighean, the sloe; R — from Greif (the tree’s name is missing in the text); A — from Elm, the fir or spruce; O — from On, the gorse or common broom; U — from Up, the bog heather; E — from Edaz, the poplar (aspen-like); I — from Idha or Ioda, the yew-tree; EA — from Eabhaz, the aspen; OI — from Oir, the European spindle; UI — from Vinlean, the honeysuckle; IO — from Ifin, the gooseberry; AE — from Amancholl, the witch-hazel; AE corresponds to Pine, the sacred pine, which was archetype for the four ‘Ifins’ (vineyard), thus, according to its kind, is the name of this branch formed..” (“The Book of Ballymote“)

The alphabetic system that emerged after the Departure of the Fairies to the Sidhe in the British Isles became known as Ogham. Although the earliest Ogham inscriptions date to the fourth century, the system probably goes back to much earlier times; nevertheless, it was for a long time rarely used for writing — indeed, the overwhelming majority of Ogham inscriptions are funerary: epitaphs and sometimes fragments of spells.

We have already noted that the Druids long avoided the use of writing for two reasons: first, they preferred to rely on their own memory rather than records, holding that only one who cannot find support within seeks it outside. Second, the very act of inscription was regarded as a magical deed, an embodiment of thought; therefore, writing was employed only in extreme cases as an adjunct to ritual action.

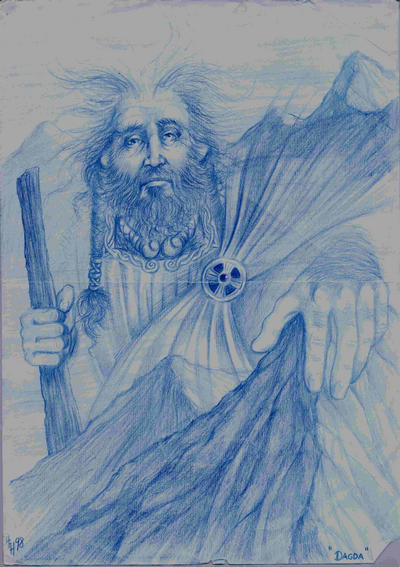

As is evident, the Ballymote book (an Irish manuscript of the fourteenth century, named for the parish where it was kept) links the origin of Ogham with the name Ogma, a god of the Tribe of Danu. There are two different accounts of this god’s origin. The cited “Book of Ballymote” connects his origin with the Fomorians: “…this occurred in the days of Bress, son of Elathan, king of all Ireland; the Creator was Ogma of the Irish line Mac-Elathan: he was the son of Dilblaz and the brother of Bress; Bress, Ogma and Dilblaz — all three were sons of Elathan. Ogham this script was called by Ogma himself. The word “ogam” comes from “gbuaim” or “guaim”, is the wisdom by which the bards gain the power of composition, because the Irish bards pronounce their poetry by means of its branches. The first verse written in Ogham is called “Soim”. It was written on bark and given to Lugh, son of Ethlenn..“.

At the same time, another Irish manuscript, the “Book of Conquests”, names Ogma as one of the sons of the great Earth-god — the Dagda.

Clearly, the “Book of Ballymote” draws explicit parallels between the emergence of Ogham and the Runes since the Fomorians — an ancient tribe of giants — resemble the Jötnar, and the three brothers — Ogma, Bress and Dilblaz — recall Odin, Vili and Vé. The likeness grows still stronger if one considers the figure of Bress — the handsome but treacherous prince of the Fomorians, whose character resembles the malevolent Loki.

Yet it is precisely this resemblance that invites suspicion, for the spirit of Ogham is altogether different from that of the Runes.

Ogham is tied to primal earthly forces embodied in the characters of the corresponding trees, and its internal logic differs entirely from the runic order. It is likely that at Ogham’s core lies the quaternary division of matter, as the Ballymote book itself indirectly indicates: “How and into what parts is Ogham divided?” — “Into four: V with its five; N with its five; M with its five; and A with its five.” The fifth subgroup of Ogham letters (the so-called “Forfeda“) consists of diphthongs and, being an addition to the first four, complements the fivefold structure of the elemental vortex that formed as humanity “matured”.

Note that in this respect the evolution of Ogham differs from the evolution of the Futharks: the development of thought, the shift from magical use to divinatory use in the case of the Runes, led to a reduction in the number of available signs (“the Younger” Futhark contains fewer Runes than the “Elder”), whereas in the case of Ogham the number of Feda increased because additional “seeds” of power were added that awaited awakening.

All this allows us to consider Ogham, after all, as the work of the Dagda’s son, whoever he may have been. Unlike scripts that developed “spontaneously,” the strict logic of the Ogham “families” has led many researchers to regard this system as having arisen at a single moment rather than having evolved gradually. Therefore, Ogma, whoever we take him to be, could quite plausibly have been the sole author of this system. Ogma’s enormous physical strength, combined with great wisdom, while bringing him close to the Primordials, may be read as an expression of the Earth’s power. The “Book of Conquests” says that Ogma fought on the side of the Goddess’s peoples in the war of the Tuatha Dé Danann against the Fomorians, slew Indecht, one of the Fomorian kings, and was later slain himself (though this did not prevent him from appearing in subsequent events).

Thus, we regard Ogham as an Earth alphabet expressing the Wisdom of Nature so revered by the Druids; its elements reduce to manifestations of the Great Goddess. Although there are many variants of Ogham script (according to the “Ballymote” — one hundred and fifty), they rest upon a common idea.

The very form of Ogham (strokes from a central axis) on one hand corresponds to marks made on a wand or a tree-trunk (signs were typically inscribed vertically from bottom to top), and on the other hand expresses the idea of the World Tree as the sum of life’s manifestations. Each “letter” (“Fid”, pl. “Feda“) conventionally corresponds to a particular force of nature that can be symbolized by a tree, a bird, a lake, and so forth. Each fid expresses a certain phase of growth and appears as “notches” on the common “trunk” — the druim — on which the whole word or sentence was “strung,” usually written from bottom to top, akin to the growth of a tree. The first three families — the Akme — express consonantal sounds, the fourth expresses vowels, and the “Forfeda” are later additions not characteristic of Old Irish.

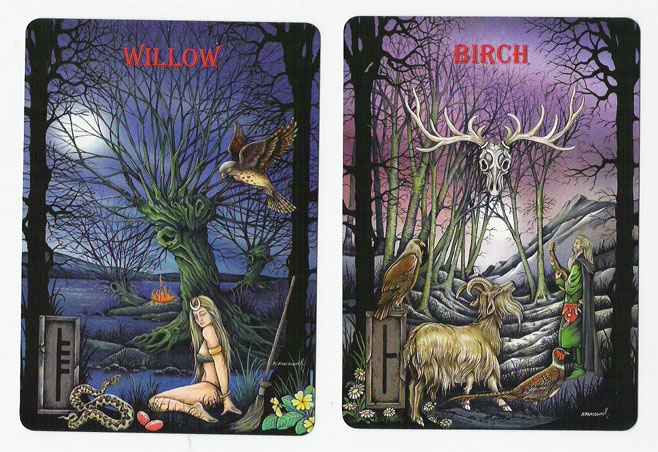

Note that the assignment of each fid to particular trees does not have strictly traceable historical roots and is largely the product of later reinterpretation of Ogham by non-Druids. However, such elaboration is entirely in the spirit of the Druidic Tradition and may be regarded not as a departure but rather as a development, a continuation of the living formation of this view of the world.

Let us briefly consider the structure of Ogham:

Thus, at the base of the Ogham alphabet lie four fives (four “Akme“): 1) Beith (birch) — the white, pure tree (aspect of the White Mother-Goddess); 2) Huath (hawthorn) — the opener of the door to the otherworld, the “May tree,” the tree of life and death in their unity, the tree of the fleshly (aspect of the Destroying Goddess); 3) Muin (“vine” — meaning any dense thicket) — the unifying aspect of the Goddess; 4) Ailm (firs, spruces, sometimes elm) — the aspect of the Goddess-Source of life and Power.

Each Akme contains plants of different ranks. There are four such “ranks,” modeled on the structure of ancient armies — “leader,” “commander,” “peasant” and “shrub.”

“Leaders” are considered to be the apple, the willow, the alder, the oak and the birch; “Commanders” — elm/vine, juniper, larch/reed, ivy and beech; “Peasants” (i.e., free subordinate warriors) — fir, aspen/tolpol, yew, hawthorn/chestnut and ash; and the “Shrubs” — the infantry, the impenetrable host — pine, hazel, maple/holly, rowan, and elder. Let us note again that “leaders” are the army’s “strategists,” making decisions but standing somewhat apart from the main battle; “commanders” are the initiating forces that sweep others along; “peasants” are the lone warriors; and “shrubs” are collective forces.

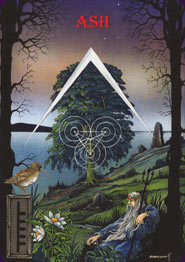

To the Five of the Birch (Beith) also belong Luis (rowan), Fearn (alder, sometimes cornel), Saille (willow) and Nuin (ash).

To the Five of the Hawthorn (Huath) belong Duir (oak), Tinne (holly, sometimes cypress), Coll (hazel) and Quert (apple).

To the Five of the Vine / Bramble (Muin) belong Gort (ivy, vine), Ngetal (reed, sometimes bulrush; in later variants Peith — viburnum), Straif (or Craif — blackthorn) and Ruis (elder).

To the Five of the Fir (or Elm, sometimes Spruce — Ailm) belong Onn (or Oon — gorse, broom), Ura (or Ur — heather), Eadha (poplar or aspen) and Idho (or Ioho, Iubhar — yew).

The fifth five are Koad (the diphthong ea — Aspen), Oi (gooseberry), Ui (or Uinllean — the diphthong ui — beech), Pethbol (viburnum) and Amancholl (the diphthong ae, sometimes Peine, Mor or Xi — pine, sometimes hazel).

Each of Ogham’s trees possesses its own unique character and properties, and a hierarchical position (“peasants,” “leaders”) described in the famous “Battle of the Trees” (“Cad Goddeu”).

Besides this “arboreal” Ogham, there were also variants, such as a “Bird” Ogham, in which the names of the signs correspond to bird names; an Ogham of Lakes (Ogham Linn), based on lake-names; Ogham Dinn, based on hill-names; and so on. All these variants proceed from the same natural logic — that all objects and places embody one aspect of a force.

Thus, Ogham offers a touch of the Powers of Nature in their primordial guise: to breathe in the magic of the woods — the Magic of the Druids — and to receive the Blessing of the Great Earth-God.

very interesting. thank you