Plants: Medicines, Power — and Poison

Modern public consciousness is conditioned to believe that plants are inherently harmless to humans and that plant-based medicines are safer than synthetic drugs.

The history of using plants as remedies dates back to antiquity, and today there is a worldwide revival of phytotherapy, which has gained many advocates. In the pharmacopeia of ancient peoples, there were over 21,000 species of medicinal plants. One of the oldest references to plants as medicines dates to the Sumerian era. A clay tablet survives that contains 15 prescriptions which historians assign to the third millennium BCE. Plants were widely used in Babylon, Ancient China, Tibet, India, Africa, and many other lands. Chinese medicine used more than 2,000 medicinal plants; India — just over 1,000. Herbal treatments were widely used in Ancient Greece. The works of Hippocrates that have survived contain more than 200 named remedies. Hippocrates believed that primary processing of medicinal plants was unnecessary, and that treatment was most effective when administered as juices or pulps.

Claudius Galen, by contrast, thought that plant material contained many unnecessary or even harmful substances. He therefore recommended extracting useful components using decoctions and tinctures of medicinal herbs.

The use of plants as remedies later spread widely among the peoples of Europe and in the lands of Ancient Rus’, and remained important in China, India, and the Arab world. The very term “phytotherapy” was first introduced by the French physician Henri Leclerc (1870–1955).

As medical knowledge advanced and new discoveries appeared, new remedies entered medical practice; many of them failed to deliver expected results or, as later turned out, produced harmful side effects. Over time they were abandoned and forgotten, replaced by new treatments. Only some remedies and methods, after lengthy — sometimes centuries-long — testing, have earned universal recognition and remain in the medical arsenal to this day.

It is believed that at least half of all diseases are successfully treated with remedies of plant origin.

However, this belief is only partly true.

When speaking of the therapeutic effect of a given medicinal plant, one must remember that the body is affected by a complex ensemble of biologically active substances (BAS) contained within it. In addition, plants contain accompanying substances that slow or accelerate the absorption of BAS. That, in turn, can lead to enhancement or reduction of BAS effects.

But are all components of medicinal plants beneficial? No — many of them are harmful and even toxic, and therefore improper use of medicinal plants, as with synthetic drugs, can produce undesirable side effects. Many plants contain not only potent toxins but also mutagens and carcinogens.

Plants are not at all happy to be torn apart and eaten; they produce many defensive chemicals that poison, repel, or disrupt the development of their predators.

So one should not assume that everything natural is safe.

Folk healers attached great importance to the time of harvesting a plant. They believed that the miraculous force of a given herb could be expected only if it was gathered at a “secret time” — at early dawn when the roosters crowed, on the day of Ivan Kupala, on Trinity Day.

The optimal time for harvesting herbs is the flowering period, which for many plants coincides with Ivan Kupala Day. Leaves’ BAS content is maximal when the leaves are fully formed but still “young.” Therefore they are harvested in late May to early June (Trinity Day).

A drawback of phytotherapy is the slow onset of its therapeutic effects, which is not acceptable in all situations. Substances isolated from plants or synthesized in the laboratory are not the same as whole-plant remedies, because their effect may differ from that of a plant decoction. This can be fatal for some patients to hold the conviction that treatment with medicinal plants can entirely replace the need for synthetic drugs.

And while the use of plants as medicinal agents — when approached with proper care and attention to subtleties — is relatively straightforward, matters are far more complex with the Plants of Power.

Many Plants of Power are the so-called entheogens or, as they are also called, psychedelics. Many of these plants grow only in the Americas, though their European relatives and analogues — better adapted to our climate — are often found.

At the same time, the terms “Power” and “biologically active substance” belong to different frameworks, and, of course, the effect of a Plant of Power is not exhausted by the effect of its BAS.

What, then, is the “Power” conveyed by plants?

Here we must pause and understand that this Power does not necessarily result from ingesting the plant or food products made from it.

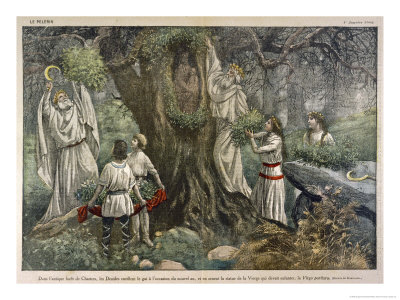

Druids long obtained the power of trees by special interaction, by attuning themselves to trees.

Although, of course, those same druids prepared many tinctures and decoctions both from medicinal plants and from Plants of Power.

For example, it is well known that mistletoe enjoyed special veneration among the Druids. Druids taught that everything growing on a tree is a gift from the heavens.

Druids believed that mistletoe could cure any disease and counter any poison. This plant — neither tree nor shrub, growing neither on earth nor on water, in the Druids’ view — treated epilepsy and ulcers, promoted conception, and protected against evil spirits. Sometimes even simple contact with mistletoe healed.

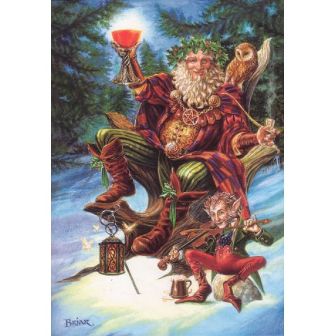

They said the plant’s most potent magical and curative properties were present at the Winter Solstice, which is why it came to be used as an attribute of Christmas decoration.

A Welsh superstition holds that beneath a hazel or ash on which mistletoe grows one could find a treasure. Yet until the 16th century, no one mentioned a hoard: the superstition then was that beneath the roots of such a tree lived a serpent with a ruby in its head. Apparently the serpent was forgotten over time, but the treasure remained. It should be emphasized that all superstitions asserted that mistletoe lost its magic power if cut with an iron or steel tool. When the Druids went to collect their sacred plant (around the time corresponding to our Christmas), they cut its branches from oaks with a silver knife. They adorned their triliths with that mistletoe.

Mistletoe is also known as the “plant of the crossroads.” The forked trunk with white berries in the center is a reminder of the ancient forked crossroads that marked a material division. The name also points to another crossroads — the Crossroads of Worlds — which is likewise associated with mistletoe.

Medicinal use of mistletoe dates back to the 5th century BCE. In the 1st century, Pliny records that mistletoe is effective against epilepsy and episodes of dizziness. Ancient herbalists considered mistletoe a remedy for stroke, paralysis, and epilepsy. Because of its parasitic growth habit, mistletoe was credited with treating tenacious parasitic growths and cancer. Hieronymus Bock (1498–1554) and P. A. Mattioli (1501–1577) claim that a mistletoe ointment heals abscesses, ulcers, and suppurating wounds, and Sebastian Kneipp recommends mistletoe for stopping bleeding and treating circulatory disorders.

But what is its Power? Druids believed that mistletoe accumulated the quintessence of the tree on which it grew, and the tree, in turn, is connected with the place where it stood. Thus, mistletoe carries both the imprint of the tree’s power and that of the place, and — when gathered correctly — can serve as a kind of “concentrate of power.”

In early Irish literature, mistletoe symbolized healing and spiritual development.

Later the plant took an honored place in witchcraft and magic: it was ascribed protective power, used in love charms, and believed to increase fertility and hunting success. Women wishing to conceive wore sprigs of mistletoe at the waist or on the wrist.

The still-popular tradition of kissing under a sprig of mistletoe at Christmas derives from wedding ceremonies that were commonly celebrated during the Saturnalian winter festivities of Ancient Rome — festivities that, with the advent of Christianity, were replaced by Christmas. Enemy warriors who met beneath mistletoe were obliged to lay down their arms for the rest of the day.

Here we clearly see two entirely different realms of mistletoe’s application — medical and magical.

Although both require special attention to the choice of plant, the time of harvest, and the ritual of gathering, their aims are completely different.

This is often forgotten, leading to a conflation of a plant’s biological effects with its magical effects.

On the one hand, using mistletoe to treat epilepsy or to guard against infertility (including by wearing it at the waist) is a medical application.

But using the smoke of burning mistletoe as a “Threshold smoke” to open a door between worlds is an entirely different application.

And here we finally reach the point that, from a magical perspective, all Plants of Power facilitate the transition between worlds — that is, they are trance-inducing, dreaming states.

As discussed at length above

Therefore it should now be clear that, in any case, Plants of Power place us on the threshold between worlds. And this carries all the advantages and disadvantages inherent in trance.

At the same time, one should not attribute all effects of Plants of Power to the psychoactive substances they contain. Although visions and hallucinations have much in common, the differences between them are even more substantial. Hallucinations are a distorted perception of the current world, external or internal relative to the observer’s mind. A vision is perception of fundamentally other worlds that live by different laws.

The same plant can produce both visions and hallucinations.

As with all approaches aimed at shifting the mind out of ordinary control, internal use of Plants of Power must be strictly regulated; otherwise, the magician turns into an addict.

A different matter is interacting with a plant’s power without damaging or ingesting it. The same mistletoe growing on a tree can provide keys to understanding without being cut, burned, or tinctured.

The same datura can aid comprehension of the nature of worlds not only as an ointment or tincture but also while the plant remains alive.

There are other examples. According to legend, the enemy of all sorcerers is St. John’s wort gathered on Ivan Kupala. If in the morning one braids a wreath of it and dances at the fire all evening, then for all 365 days of the year, the person will be protected from the Evil Eye. If one weaves and wears a belt of St. John’s wort, it will take upon itself all the evil; and if the belt is thrown into the fire on November 1 (Samhain), all the evil accumulated on the belt will return to the sender.

Among the people, there was a belief that the linden tree protected from lightning. A person standing under a linden during a storm need not fear thunder or lightning.

The Greeks believed that aconite grew from the foam that fell from Cerberus’s mouth. Growing in the garden, aconite protects the territory. Its tuber, carried in a pouch on the chest, brings luck.

On the graves of sorcerers and cursed people, thistles were planted to prevent unclean spirits from dragging their souls to Hell.

And there are many such examples.

It is believed that internal use of a Plant of Power was employed only at the outset of practice, to free the mind and assist in the initiatory emergence of the shaman into other worlds. Constant use of Plants of Power was considered a bad habit and regarded as possession by a harmful spirit.

Summarizing the foregoing, one can draw a number of conclusions:

1) The use of plants as medicinal agents requires no less caution than the use of synthetic drugs;

2) Although Plants of Power often contain biologically active substances, one must distinguish between pharmacological effect and the effect of Power in their action;

3) Receiving Power does not necessarily imply ingesting the plant;

4) Internal use of Plants of Power requires the same measured approach as other trance practices.

This article is quite interesting, but I would like more practical information. Everything said above is only useful for those who are just starting to study this topic.

Wonderful article. Thank you