Life as the Great Attractor. The Eleusinian Mysteries

At the end of the Bronze Age Collapse, when humanity sought new ways of becoming aware of itself and its place in the world, proto‑Greek civilization produced two unique transformational systems aimed at attaining wholeness of consciousness. It was at that time that the Orphic mysteries developed in the eastern Balkans — intended, as we have discussed, to synthesize the Apollonian (rational, ordered) and the Dionysian (elemental, flowing) principles — while on the western Peloponnese an equally coherent and effective Eleusinian system took shape.

The Eleusinian rites are the oldest and most enduring mystery cult of Hellas, surviving for almost fifteen centuries and becoming the true heart of the Greek “religion of the soul.”

The roots of the cult of Demeter at Eleusis reach back to the Mycenaean era (14th–13th centuries BCE), when on the site of the future Telesterion there stood a pre‑Hellenic sanctuary dedicated to the Great Goddess of life and fertility. Eleusis was then an independent polis, and the cult of Demeter a local, maternal‑chthonic cult.

In the Archaic period a war erupted between Athens and Eleusis in which the kings of both poleis died: the Athenian Erechtheus (by Zeus’ will) and the Eleusinian ruler (Immár or Eumolpus). The result was a special union whereby Eleusis was incorporated into Attica while retaining its cultic autonomy. Already then the ancient priestly houses of the Eumolpids and the Kerykes became the rightful custodians of the mysteries, even as Athens became the political center.

In the 8th–6th centuries BCE the “canonical” form of the mysteries crystallized: a clear sequence of initiatory grades was established — from the “closed” (μύστης) to the “seer” (ἐπόπτης) — and a strict prohibition against disclosing anything concerning the Mysteries took shape.

In the 5th century BCE, under Pericles, the principal hall of the mysteries — the Telesterion — was rebuilt by the architect Ictinus: it became a vast chamber designed to hold thousands of initiands. It was then that the mysteries became a pan‑Hellenic center, drawing not only Athenians but Greeks from other poleis.

In the Classical and Hellenistic periods many cultural figures underwent initiation in the mysteries, among them philosophers — Plato, possibly Aristotle, Plutarch — and poets — Aeschylus, Sophocles, Pindar — and politicians — Pericles, Solon (at least as patrons and participants); later, Hellenistic and Roman rulers followed suit.

In Roman times Eleusis enjoyed special imperial patronage. Among those initiated were Octavian Augustus, Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius, and later Julian the Apostate. Augustus, once initiated, supported the sanctuary and at the same time restricted access to the mysteries for ordinary Roman officials, emphasizing the emperor’s special status. Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius financed restorations of the complex; Julian sought to make Eleusis a pillar of his revived “Hellenic piety.”

The inner meaning of all Hellenic mysteries — Eleusinian, Orphic, Dionysian, Kabiric — can be reduced to the aim of “gathering” the soul: restoring its genuine wholeness and thereby attaining immortality. The Greeks understood that the ordinary human psyche is fragmented, liable to dissolution, and after death subject to the same dispersal as the body. By these accounts the soul “as it is” in the ordinary person is not immortal; only the assembled, integrated, purified center of the soul is immortal.

And it is precisely for this purpose that the mysteries were enacted.

From the standpoint of Greek ontology, the human “soul” consists of several levels, largely analogous to the ancient Egyptian ḥeperu: psuchē — the vital soul, breath (mortal); menos / timos — the passionate, reactive soul (mortal); nous — the intellectual, lucent principle (which can be immortal, but only after purification); eidolon — the shade, the image of the soul that wanders in Hades (also unstable); Daemon — the higher guide, which is rarely accessible to man.

Meanwhile, the “ordinary” soul after death disintegrates: part of it goes into the “shade” (eidolon), part dissolves into the common spirit, part dies definitively. That is the fate of the “uninitiated.”

The mysteries were, however, aimed at the “assembly,” the reintegration of such a dispersed soul — at uniting the psyche into a single vessel. To that end they employed various versions of the common Myth of death and rebirth: the experience of symbolic dying and the subsequent return of a transformed soul that has found its integrity. During these experiences the mind was brought into contact with the divine, entering a level of being that is not subject to dissolution, and acquired an inner “seed” capable of surviving Hades, what the Pythagoreans called the “σπέρμα αθανασίας” — the “seed of immortality.”

It is precisely this “seed‑like” transpersonal aspect that made the mysteries a universal instrument of salvation, regardless of the specific ritual form.

And in this respect Eleusis occupied the pinnacle for Classical Hellas. Yes, the Orphic and Dionysian mysteries carried great weight, but Eleusis possessed unquestioned authority as a “bridge” to blessedness in the afterlife. For the Hellenes it was the central path to the soul’s immortality, the guarantor that the psyche — the “disintegrating vessel” — could be gathered into a single center.

It may seem paradoxical that the pinnacle of the mystery tradition was precisely Eleusis, grounded in a “maternal” myth, since in modern discourse the maternal principle is usually associated with generation, dissolution, immersion in the flows of nature or return to the earth’s womb, and not with centering, which is commonly perceived as a function of a “paternal,” solar, Apollonian principle.

However, from the perspective of the ancient Hellenes the maternal principle supplies the deepest center. Demeter is not the dissolving Great Mother but the Goddess of Law who passes through loss to restore order and thereby bring souls back to life. Namely, the power of Eleusis is feminine in that it gathers what has fallen apart; from this point of view the center is the result of attraction and retention, which is regarded as the Mother’s function. The female axis Demeter–Persephone, forming the core of the mysteries, undergoes dissolution (like Dionysus), restores form (like Apollo), and — importantly — also maintains cohesion, like the preservation of memory, like retention. And it is precisely this that can bestow immortality as an unbreakable wholeness not subject to dissolution.

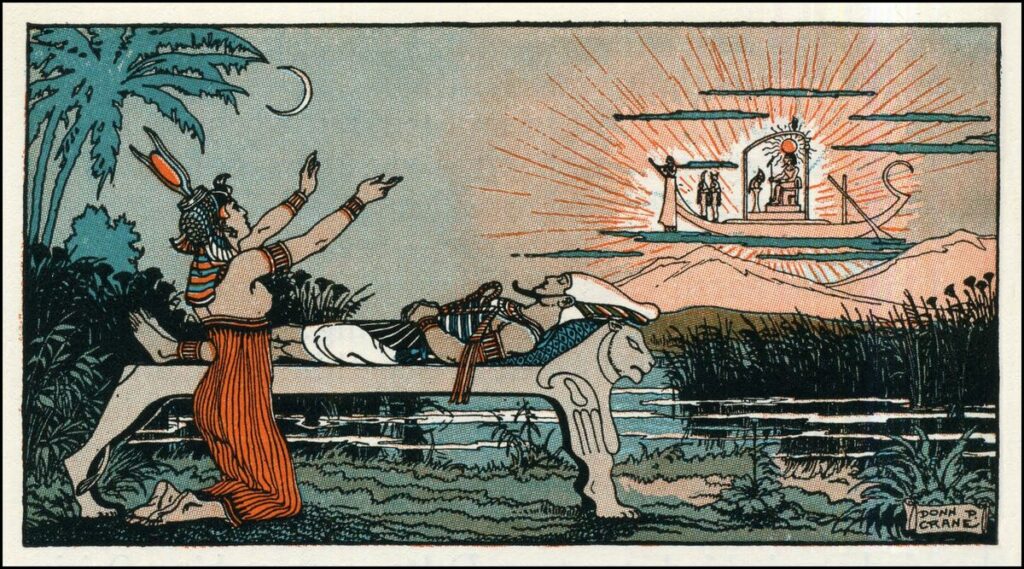

The Eleusinian mysteries as a means of attaining wholeness are often compared with the Egyptian myth of Osiris and Isis. On the level of ritual mechanics they are indeed two versions of the same path of the soul to wholeness through dissolution, search, gathering and return. In both systems the feminine is a special organizing field that makes possible the re‑creation of an eternal structure (the body of Osiris, the initiate’s soul, the cycle of nature). From both perspectives the human soul attains eternity when its “parts” are assembled into a new, deathless configuration. The Egyptian Way conceives the soul’s wholeness as the unity of the body — an object restored and thereafter existing in eternity. Egypt had no separate “maternal” mystery because Egyptian religion as a whole was inherently maternal and chthonic in structure. In Greece, by contrast, the feminine principle required a distinct mystery to assert its power. For the Greeks the soul is a process, hence the personification of the recreated psychic axis is a female figure: fundamentally a stream, a movement, a passage, while the Feminine is the principle of coherence and attraction.

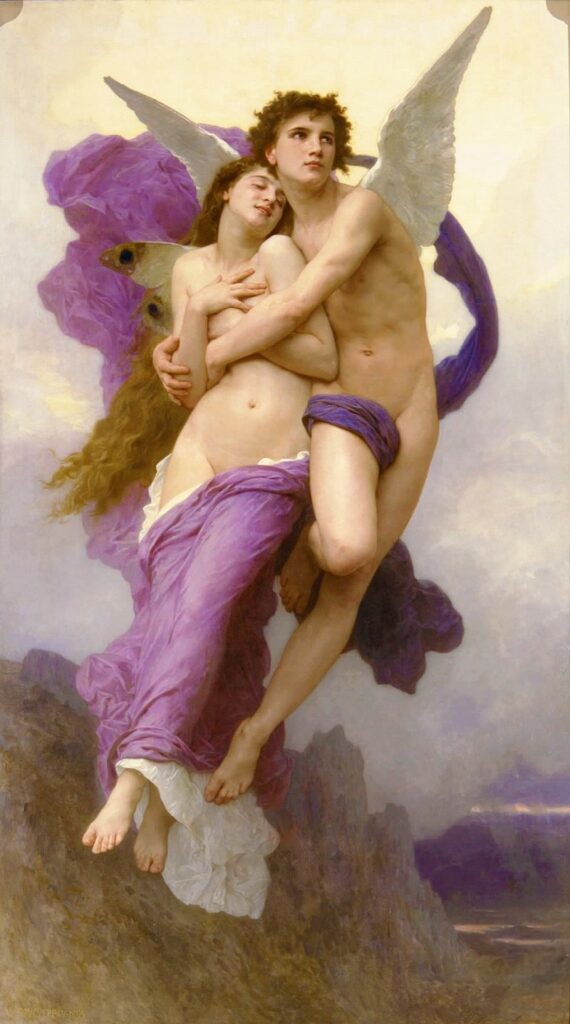

Similarly, the myth of Demeter and Persephone can be compared with the myth of Eros and Psyche (if one understands Eros in the broadest sense as the force of attraction, a metaphysical “gravity,” and Psyche as “soul” in a general sense). In both myths the soul is scattered, “mortal,” plunged into darkness, and there exists a force that prevents its disappearance.

The Greeks clearly distinguished two poles: Gaia (Γαῖα) as the cosmogonic ground, the earth as being itself, mass, matter — the “body of the world,” which does not yet organize but simply exists — and Demeter (Δημήτηρ) as the already‑structured Earth, order, the stages of sowing and growth, the earth that has acquired the function of law (nomos) of nature. The ancient form of the name — Ge‑meter / Γη‑μήτηρ, “Mother‑Earth” — shows that Demeter was originally a form of Gaia, her later, more structured and initiable hypostasis. In a mystery reading, Demeter is Gaia revealing the law of integration. In the mysteries Demeter performs a function impossible for Gaia, since Gaia is not a mother in the personal sense, not an image, but the primal substance of the world with which one cannot enter into a personal, ritual, initiatory relationship. Thus the cult of Gaia is archaic, not mysterious, whereas the cult of Demeter is deeply mystical because she “gives form.”

In Kabbalistic terms one might say that Demeter is Chayah(חיה), Great Life — the force that holds the soul in its form until it reaches the yechidah — while Persephone is the neshamah, the “soul” as such. In this context the primordial Goddess — Night (Nyx) — is Bina / Atzmut / the Dark Mother (an abyssal potentiality yet unformed), and Demeter / Chayah / the lower aspect of Bina is the maternal aureole of Life, the life‑field that gathers together the soul’s scattered parts.

Thus, in the most general sense, Demeter is the maternal principle of form, matter as the receptacle for the soul. She is the center of attraction that seeks the lost light, calls it back, creates the conditions for its return — a integrating force that gathers the dispersed parts of the psyche and transforms “mortal multiplicity” into a stable form. In this sense Demeter functions as an attractor: a center toward which the scattered soul is inevitably drawn, even when part of its nature is bound to Hades.

In modern psychological terms, Demeter is the “holding environment,” the psyche’s capacity to endure its own experiences without collapsing into chaos; the ability to live through pain, anxiety, and disintegration without repression. This aspect explains why she searches for Persephone: the shadow of loss or the “fall” of the soul can be healed not by annihilation but only by compassionate attention.

For Jung the Great Mother has two poles: generative and devouring. Yet Demeter is a third aspect: the mother who neither merely gives birth nor simply absorbs, but restores lost unity. She is the maternal archetype as structuring energy — what returns the dispersed parts of the “I” to a single center.

And, by analogy with the Osiris‑Isis myth, one can say that in the symbolic representation of the mysteries Demeter is the physical body that seeks and returns its soul — Persephone. The Greeks did not regard the body (soma) as mere “matter”; for them it was a means, a structure in which the soul could manifest. Persephone in Hades is the soul in the depths of the unconscious, in the world of shadows, in a condition of “dissolution” and loss of center. When the soul returns to the body, wholeness arises, providing the possibility of immortality. Therefore Plato employs Eleusinian symbolism in the Phaedo, explaining how the soul unites with bodily form and becomes “active,” “eternal,” and “self‑sufficient.”

From this vantage point, Persephone is the personal aspect of Gaia, transformed by Demeter — the soul that undergoes death and return. Her state is not an accidental “fall” but the natural and lawful condition of the human soul: already divided between light and darkness — “part of the year above, part below.” That is, in Greek thought the soul is not originally whole; its “orbit” is unstable.

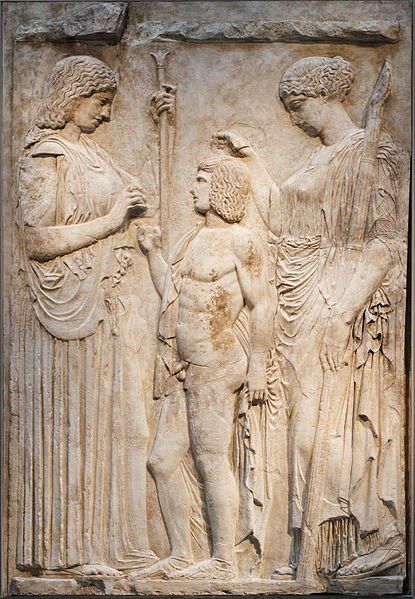

Persephone is the daughter of Zeus just as the soul is the “spark of God,” in Plato’s words: “Souls originate from Eternity and partake of the Divine Mind.” Persephone’s Return is the “illumination of the soul,” the “anagoge” — the soul’s return to mind (Plato). Thus the myth of Persephone tells of the soul as a “spark of God” descending into matter and returning to its divine source. The second name — Kore (κορά – “girl”) — means the Soul before descent: innocent, undivided, unaware of death; while “Perse‑phone” (Περσεφόνη) means “she who brings light (phos) through destruction (perthō).”

One can also draw an analogy with the Gnostic myth: from the Mother (Demeter, Sophia) a Daughter — pure soul, “light‑bearing” — is born of the Heavenly Father (Zeus) and then descends into the “world of darkness” (Hades, the “Invisible,” where there is no light), but can be raised from there and returned to its original nature. That ascent constituted the goal of the Gnostic anabasis and of the Eleusinian epopteia.

Structurally the mysteries had two stages:

· The Lesser Mysteries (at Agrae, in spring) — preparatory purification.

· The Greater Mysteries (at Eleusis, in autumn) — the actual initiation, the culmination.

During this process the participant progressed from the status of mystēs (“closed,” not yet seeing) to that of epoptēs (“the seer,” one who has seen).

The Greater Mysteries lasted approximately nine days and included several mandatory stages.

· Preparation and purification

– proclamation of the beginning on the Athenian agora;

– bathing in the sea, ritual cleanliness;

– the sacrifice of a piglet as a substitute for ancient human offerings;

– fasting, abstinence, restriction of speech.

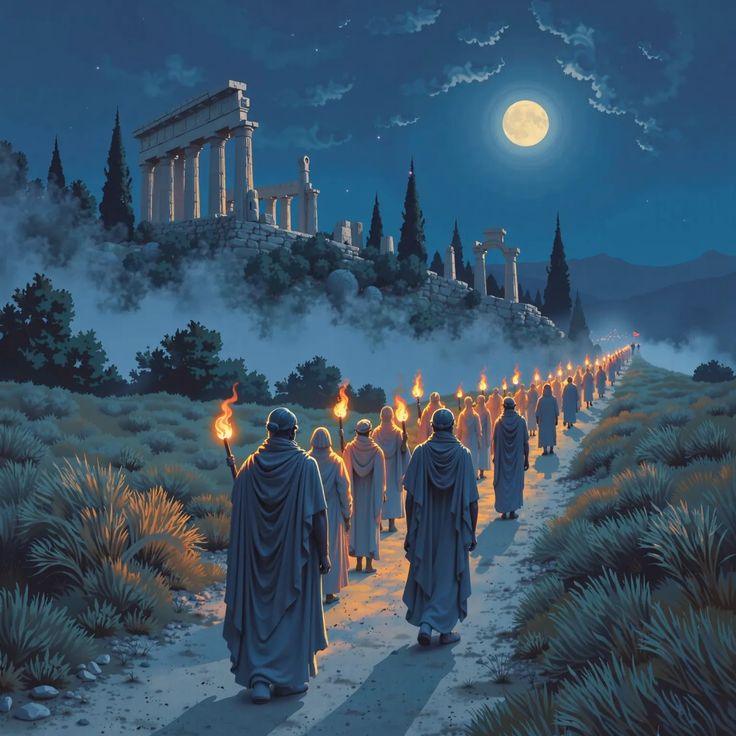

· The torchlight procession

The nocturnal torch procession from Athens to Eleusis reenacted Demeter’s search for her daughter: the participant literally enacted the archetype of “seeking the soul in darkness.”

· Entrance into the Telesterion and the “descent.” In the vast hall‑refuge — the Telesterion — the climax was staged: a controlled death of consciousness through sensory disorientation, fear, and loss of bearings, which forced the ordinary “I” to disintegrate.

The classical triad (Μυούμενα) of methods included:

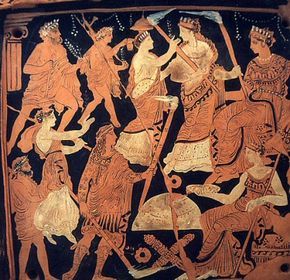

- dromena — the “performed”: ritual acts and staged episodes of the Demeter–Persephone myth;

- legomena — the “spoken”: sacred formulas, cries, brief explanations;

- deiknemena — the “shown”: the display of sacred objects.

After darkness and shock a sudden light and the showing of the sheaf followed. Ancient authors describe this as a transition from a nightmarish, chaotic state to “a clear space with meadows and light.” This experience was understood as a “posthumous awakening” and the vision of true form.

Three symbols were used as supports for the mystery experiences — the bull’s skull, the flower, and the sheaf — representing three stages of the life cycle through which both nature and the human soul pass. The bull’s skull (or calf mask) expressed death, sacrifice, the descent of the soul; the flower (often the narcissus) signified awakening in another reality, a summons but also temptation; the sheaf of wheat (or barley) symbolized rebirth, fruit, light, and return. At the end of the mysteries the famous phrase was uttered: “Ὁ Κύριος ἔσπειρεν, καὶ ὁ Κύριος ἔθερισεν” (“The Lord sowed — and the Lord reaped”), meaning that the soul had been sown into the body, passed through death, and returned transfigured. The sheaf is the image of the soul’s attained wholeness, its “new body,” analogous to the sah in Egypt.

Another important image in the Eleusinian mysteries contrasted the pomegranate as the “disharmonious,” “mortal” assembly of the psyche, and the sheaf as its perfected structure. The pomegranate was understood as many seeds contained within a hard shell, while the sheaf was many seeds “strung” upon a single stalk. In other words, the pomegranate is multiplicity that drags the soul downward — seeds within a dense, red, closed vessel surrounded by darkness and moisture or blood. Thus for the Greeks the pomegranate symbolized the soul’s descent into matter, the world of desire and entanglement, its succumbing to the pull of the flesh and, as a result, its sinking into a dark multiplicity. The sheaf, by contrast, is multiplicity that lifts the soul upward: multiplicity gathered into a vertical, luminous Unity. When the sheaf ripens the soul does not disperse but perfects; it is the symbol of the Idea that has passed through death and been gathered into a new form. In the images of the Eleusinian Myth, Persephone reaches for the flower, then tastes the pomegranate and descends into darkness, but subsequently turns back and returns transformed as a sheaf — this is what manifests as epopteia (illumination). At the highest stage the priest silently showed the initiates a pure sheaf (this was called “Deiktika,” the “Showing of the Sacred”), and that was the epopteia — the vision of the “Higher Form.”

Overall, the mysteries involved intense experiences, for the induction of which the Mystagogues induced in the initiates a special state of mind in which transformation occurred through the successive passage of death, darkness, illumination and return. As they said, “The Mystery acts not by words but by a state” (ἔργα, ἀλλ’ οὐ λόγοι). Plutarch describes: “At first — wandering in darkness, fear, streams of sweat.” This was the psychological death necessary to rupture the former “I.” Then came the “abduction of Persephone” — a “violent” severing of sensory perception and sensory disorientation. Priests created absolute darkness from which terrifying sounds, sudden flashes of light, odors, gusts of air, jolts, and various thermal effects were emitted. Consciousness passed into a particular altered state, a kind of dynamic trance. Thus the initiate lived the myth of Persephone as their own story: the loss of the soul, its search, dissolution, wanderings and new recovery.

According to Plutarch, “Then suddenly a clear space opens, light, meadows, hymns,” that is — the illumination arrives.

And this was followed by the aforementioned act of “showing” (δείξις) of the pure form — the symbol that gathers inner chaos into a single center, a direct encounter with a “visible Idea.”

Next came the ritual drinking of a special brew of barley and mint — kykeion — which was meant to ease the altered state, soften the transition and at the same time intensify the sudden light. This was a “sharing of the cup” with Demeter, an acceptance of the natural order of life and death.

All this culminated in the supreme experience of meaning about which Cicero and Isocrates wrote: “We learned not only how to live, but how to die.”

As a result of the mysteries the initiate gained a deep sense of the soul’s immortality and stability, their fear of death vanished, and acquired new knowledge of the life cycle as well as inner cohesion. This was precisely the unification of the soul’s scattered parts that expressed itself as the return of Persephone.

In sum, the core of the Eleusinian tradition can be described as follows:

The human soul is originally split between light and darkness, above and below, divine and material. In this state it is “mortal”: unable to endure death without disintegration. This fragmentation appears in the psyche as conflicts, dependencies, losses, a sense of meaninglessness and fear of death.

The maternal principle (Demeter) is the memory of wholeness and the force that attracts the parts to one another. It will not allow the world and the soul to “freeze in winter”; it demands Persephone’s return and the “resurrection” of the world. In the form of the goddess the maternal principle gathers and integrates her, returning her to the source.

Life‑as‑Attractor — is the deep sense and striving for wholeness that does not vanish even when the mind is plunged into the Hades of habitual patterns, dependencies, traumas and oblivion. The soul may descend into darkness, pass through many lives, trials and deaths, but the very movement of return is possible only because there exists in the structure of the world something that awaits it and draws it — the maternal field of Life. Mother‑as‑Great‑Attractor and Eros are two aspects of a single cosmic force, the supreme gravity of Chayah — an integrating attraction and a directed love, both background and vector.

In this sense the Eleusinian initiation is the attainment of an inner form that makes the soul more whole and less mortal than it was: it becomes capable of sustaining itself as a unity even against the backdrop of the body’s and the world’s dissolution.

In the article, you mentioned that the ancient Egyptians had a different attitude toward the maternal principle than the Greeks. However, the main gods of Egypt are also male – Ra, Amon, Osiris. Why do you say that Egyptian religion is more “matriarchal”?

The attitude of Egyptians and Greeks towards the maternal and paternal principles is indeed different. For the Egyptians, the Sky is feminine, Nut (or Naunet in a more chthonic sense), while the earth, on the contrary, is masculine – Geb. For the Greeks, on the contrary, the Sky – Uranus – is perceived as a masculine principle, while the Earth – Gaia – is seen as feminine. This is not a contradiction, but simply different points of view: for the Egyptians, the Sky is the environment in which the Sun (Hathor – “House of Horus”) lives and acts, while the Earth is a solid support on which the world firmly stands (and therefore Geb is a male deity). The Egyptians saw a “stone-like,” solid image of the Earth in their desert areas. For the Greeks, on the contrary, the Sky is the principle of fertilization, from which rain and warmth come, providing the process of life, while the Earth is the medium, the substrate from which this life is built. Therefore, in the country where the Sky is Uranus (male), the world is male logos (Zeus-Apollon), only a separate mystery (Eleusis) proclaimed the importance of the maternal archetype. In Egypt, “maternal” festivities were known, for example, the “Nights of Hathor,” rites of intoxication, ecstasy, and music. But this was not perceived as a path of death-return, but as a path of returning life force (sexuality, energy, celebration). In Sais, in later times, mysteries of Neith (Sais) were also held, and this was one of the greatest temples, where, according to Herodotus, “only a few were admitted.” However, this was not a female mystery, but a magical school where geometry, cosmology, cosmogony, metaphysics were studied. Therefore, these “mysteries” are much closer to Platonic rational gnosticism, to nous, than to Eleusinian experiences. Overall, Egypt is much more “maternal” than Greece, since if for the Greeks the feminine is a part of the system, then for the Egyptians the feminine is the system itself. The creator of the world, the god Atum, is the unified principle before the division into male/female, so even “male creation” in Egypt is not separated from the female. For the Egyptians, the world is immersed in the feminine, and the masculine is only a ray of light in the maternal flesh of the cosmos.

Hello. Can we say that Demeter is a kind of black hole, a region of singularity, syntropy? Is the Egyptian Aida the same?

Hello! No, in my opinion, Demeter in this sense is rather an organization of the “gravitational structure” of the universe, by which the Universe acquires ordered movement.

Thank you for the article! And thank you for your work, dear Enmerkar!

It can be added that Demeter is, first of all, the founder of the cult. For those interested, a setting similar to the Telesterion can be found in the mosque in Cordoba (specifically wandering in the darkness of the mosque and emerging into the light in the church).

How is Persephone’s cyclical reign in Hades interpreted in the context of the mysteries? Is it a repeated regular fragmentation of the soul?

No, it is seen as a new birth again in the darkened world, which requires new “assembly” and new resurrection.

Thank you very much for the fascinating article.