Druids and Human Sacrifice

Alongside the well-known and indisputable wisdom of the druids, the literature about them often contains indications — veiled hints — of human sacrifices they practiced.

It is well known that the druids and the religion they represented had, by the beginning of the 1st century CE, become the object of a series of repressive measures by the Roman authorities. According to Suetonius, Augustus forbade Roman citizens to adhere to the druidic religion. Pliny recounts how, under Tiberius, the Senate enacted a law against the Gallic druids “and all diviners and healers of that sort.” As Suetonius reports, Claudius in 54 CE “completely extinguished the barbarous and inhuman religion of the druids in Gaul.”

Knowledge of the druids, their place in Celtic society, and their principal functions comes primarily from ancient sources, among which the sixth book of Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic War is rightly considered the most interesting and complete. It contains the following description: “The druids take an active part in the worship of the gods, they oversee proper performance of public sacrifices, and they interpret all questions relating to religion; many young men come to them for instruction in the arts, and generally they enjoy great prestige among the Gauls. It is they who pronounce almost all decisions in disputed matters, public and private; whether a crime or murder has been committed, whether there is a dispute over inheritance or boundaries — these same druids decide; they also assign rewards and punishments; and if anyone — whether a private individual or a whole nation — does not submit to their decision, they exclude the guilty from sacrifices. This is their severest punishment. One thus excluded is deemed impious and outlawed, everyone shuns him for fear of misfortune, as though from contagion; however much he may plead, he is denied legal recourse; he has no claim to any office. At the head of all the druids stands one who holds the greatest authority. Upon his death the most worthy succeeds him, and if there are several such, the druids decide by vote, and sometimes a dispute over precedence is even settled by arms. At a certain time of year the druids assemble at a consecrated place in the territory of the Carnutes, which is regarded as the center of all Gaul. Here all those engaged in litigation converge from everywhere and submit to their decisions and judgments. Their learning, it is thought, originated in Britain and was brought from there into Gaul; and even now, in order to study it more thoroughly, they go there to study. The druids generally do not take part in war and do not pay taxes like other people; they are free from military service and from all other duties. Owing to these privileges many enter their schools partly of their own accord and partly sent by parents and relatives. There, it is said, they learn many verses by heart, and thus some remain in the druidic school for twenty years. They consider writing verses down sinful, whereas in almost all other cases, in public and private records, they used the Greek alphabet. It seems to me that this practice is established for two reasons: the druids do not wish their doctrine to be made public and they think that, were their students to rely too much on writing, they would take less trouble to strengthen their memory… Above all, the druids teach the belief in the immortality of the soul: according to their teaching, the soul passes after death from one body into another; they believe that this faith removes the fear of death and thereby inspires courage. Besides, they teach their young pupils about the heavenly bodies and their movements, about the size of the world and of the earth, about nature and about the power and authority of the immortal gods“.

Caesar writes that the druids not only took part in sacrifices but also oversaw their proper performance and presided over the religious life of the Gauls. Caesar then describes the burning of people destined for sacrifice, though he does not mention the druids’ participation in the act.

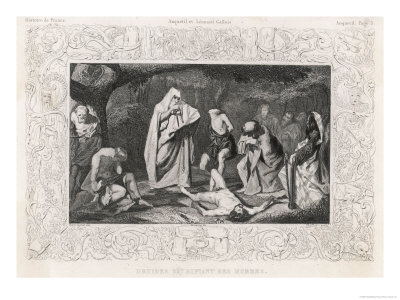

Strabo, in Book IV of his Geography, wrote: “The Romans put an end to their (the Celts’) cruel rites, and they oppose sacrifices and prophecies so unlike our own. Thus a man destined as an offering to the gods is struck in the back with a battle dagger and then, according to the convulsions of the dying man, the future is foretold… All this is always performed with the druids’ participation and authority.” Strabo also described the custom of cutting the victim’s body into pieces and hanging them on sacred trees or on the walls of temples. There was also a ritual according to which the victim was drowned, buried (ingummation), stabbed with a knife or spear, and so on. “Accounts are given of other forms of human sacrifice: unhappy victims were killed with arrows, impaled on stakes in temples, or a colossus of wood and straw was built, into which domestic cattle, all manner of wild beasts, and people were thrown and the whole burned as an offering.”

Lucan, the Roman poet of the 1st century BCE, noted that in Gaul a victim was hung on a tree for the god Esus, burned alive for Taranis, and drowned in a cauldron for Teutates.

Diodorus Siculus concurs: “They — and this displays the savagery of their nature — behave like habitually godless people when it comes to sacrifices. For example, they have the custom of imprisoning all criminals for up to five years, and then, to honor their gods, they impale them and sacrifice them, adding many other offerings and burning everything together on huge, specially prepared pyres. From prisoners taken in war they also make unfortunate martyrs offered in sacrifice to the gods.”

Yet Homer likewise depicts how the king of the Greeks, Agamemnon, sacrificed his own daughter during the Trojan War in 1180 BCE, and how captives — Trojans — were burned on Patroclus’s funeral pyre. There is no basis for claiming that in Homer’s lifetime the Greeks were regarded as uncivilized people who practiced human sacrifice. Even in classical times, before the Battle of Salamis (480 BCE), the Greeks sacrificed three Persian captives to Dionysus. A century later, before the Battle of Leuctra (371 BCE), the Thebans, persuaded by Pelopidas’s dream, were prepared to sacrifice a fair-haired girl, but at the last moment substituted a white mare.

The Romans of the Republican era were likewise not averse to human sacrifice in emergencies in exceptional circumstances, such as Hannibal’s invasion of Italy. But already in 97 BCE all forms of human sacrifice in Rome were prohibited and thereafter regarded as a barbarous custom. It was later forgotten that the gladiatorial combats so popular in Rome originally had a ritual character and represented a kind of offering to the god of war.

Pliny, recounting how Emperor Tiberius “pursued the druids,” tells his provincial friends that the priests’ power had finally ended and that the cruel rituals, inspired by the false doctrine that the gods delight in brutal killings and cannibalism, had passed into the past.

Well known too is the human-shaped cage made of willow wands, the “Wicker Man,” which, according to Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic War and Strabo’s Geography, the druids used for human sacrifices, burning it with people locked inside — those condemned for crimes or destined as offerings to the gods.

In Caesar’s time the annual Carnute assembly took place — a representative gathering of druids endowed with extraordinary religious and judicial authority. A particular sacred site was chosen for the assembly. This main sanctuary of the Gaulish Celts was located on the territory of the Carnutes (near modern Orléans), because that area was regarded as the center of all Gaul.

The Carnute assembly began with a public sacrifice. When the Roman poet Lucan spoke of the dreadful blood offerings to the great Gallic gods Teutates, Esus, and Taranis, he most likely had in mind the religious ceremonies performed on Carnute soil. From Lucan’s text it is quite clear that people were offered as sacrifices. Diodorus, Strabo, and Caesar likewise reported on human sacrifices presided over by druids. It appears that all these authors referred to the same religious rites carried out during the Carnute assembly.

At the Carnute gatherings the druids conducted not only religious ceremonies but also legal proceedings. This was the distinctive character of the Carnute assembly. According to Caesar, the assembly functioned above all as a kind of all-Gallic court: “Here all those engaged in litigation converge from everywhere and submit to the decisions and judgments of the druids.” The Gauls voluntarily and willingly appealed to the druidic court, which provided an alternative to unfair magistrates’ courts and was, moreover, invested with the high religious authority of the priests. Both whole communities and private individuals brought their disputes before the druids. Druids dealt mainly with criminal cases involving homicide, but they also handled matters of inheritance and disputes over boundary demarcation. The druidic tribunal fixed the weregild the killer had to pay. If the guilty party was unable or unwilling to pay the sum established by the druids, they determined the measure of punishment.

At the same time, the “exclusion from sacrifices” that Caesar described was perceived by the ancient Celts as the gravest punishment: expelled from society, such a person lost the opportunity to participate in the cult and were thereby cut off from communal rites. It is unlikely that those tormented by “cruel druids” would have feared being cut off from the cult.

The high authority and sacred significance of the Carnute assembly are explained by the fact that its rites included the most important ceremonies that reproduced a cosmogonic act. The Carnute assembly took place at a certain season of the year, and that season was a projection of the mythical primordial time when the world was created. Moreover, Caesar states that the ceremonies of the Carnute assembly were performed in a “consecrated place.” Thus a connection was established between sacred time and sacred space, in which the Cosmos is often compared and identified with cosmic time.

Perhaps the human sacrifices at the Carnute assembly imitated an original offering made “at the proper time” to give life to the whole world. Finally, the justice administered at the assembly was equated with the cosmic order.

On one of the plates from the cult cauldron found near the site of Gundestrup in Denmark, a giant figure is depicted lowering a small human headfirst into a cauldron. For a long time this image was interpreted as human sacrifice by drowning. A comparison of this scene with the text of one of the Welsh epic traditions allows the suggestion that the plate shows a miraculous cauldron of life into which fallen warriors were placed so that on the following day they would be resurrected and take part in battle again.

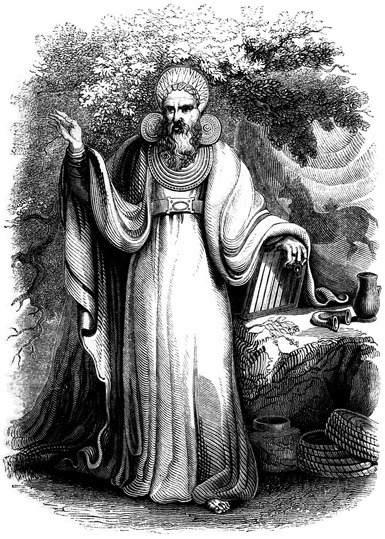

Such interpretations led some modern scholars to attempt to absolve the druids of responsibility for human sacrifices. Thus the druids are defended by the French researcher Françoise Leroux: “In any case,” she wrote, “the image of a druid sacrificing a human being on a dolmen is purely a product of imagination.” She commented on the accounts of classical authors (Caesar, Strabo, Diodorus, etc.) as follows: in Irish and Welsh traditions it is very difficult to separate history from mythology; the classical authors did not understand this and therefore exaggerated the significance and reality of human sacrifices among the Celts. Gaul and Britain seemed to Caesar’s and Augustus’s contemporaries like fairy-tale lands, and therefore the most incredible rumors circulated about them.

The English scholar Nora Chadwick also attempted to exonerate the druids. In her view, nothing in Strabo’s text indicates the druids’ active participation in this ritual. They supposedly merely attended the sacrifices, “as officials supervising the ritual’s execution and preventing its improper conduct.”

Opposing this view was the Scottish scholar Stuart Piggott. Having examined the evidence of the classical authors objectively and regarding them as credible, Piggott considered it completely unjustified to “remove” the druids from participation — quite possibly active — in beliefs and rites that included human sacrifice. The druids, he argued, were the priests of Celtic society, and Celtic religion was their religion with all its cruelties. Piggott ridiculed the notion that “the druids, present out of duty at the performance of sacrifices, stood with disapproving faces, immersed in lofty thought.”

At the same time, the classical authors emphasized that human sacrifices occurred only in times of great danger.

The view that the sacrifice was, as a rule, expiatory and protective seems justified. It was always a most complex ritual, the necessity of exact execution of which was dictated by its profound sacred meaning. In the sacrifice the deity itself was, for a moment, embodied and slain by the priest, only to be resurrected. This was the social and spiritual essence of the ritual of sacrifice, which ensured the continuation of time and sustained its natural course.

Thus, a survey of the sources and their comparison with the spirit of druidism support the assertion that human sacrifices — committed only in exceptional cases, in times of grave danger or for initiatory mystery rites — were portrayed by Roman propaganda as if they were a routine practice of druidism and as evidence of the cruelty and uncivilized nature of the Celts in general and the druids in particular. The Roman state saw in the druids its chief adversary on Gallic soil. The apparently exaggerated “cruelty of the druids” most likely stands as one of the earliest examples of distortion of reality for propagandistic ends.

In Irish literary sources (the treatise “Dinnsenchus”) there is also mention of bloody human sacrifices by the Celts. Such sacrifices were made once a year in the cycle on the eve of Samhain … here’s a brief quote:

“There (i.e., in Mag Slecht) stood the king of the idols of Erin, named Cromm Cruach, and around him towered twelve other stone idols; Cromm Cruach himself was made of gold. The people brought him firstborns and beginnings from every thing, as well as offspring from the leaders of each clan.”

Of course, all these testimonies present an outsider’s view, and all the more “wild” it seems to an observer from our civilized European-Christian time … however, for the Celts, this (sacrifice) apparently had a completely different meaning, and sacrificing part for the whole was accepted as an inseparable part of existence. But that does not mean that in this time such practices are justified … modern society has shifted the center of its perception towards selfishness; members of society form only a crowd, but not a unified whole … thus the concept of sacrifice has shifted into the inner world of a person, and if anything should be placed on the altar, it is one’s own “values.”

Therion, what was the goal of the quoted treatise? If this is a propagandistic work of monks, then it should be treated accordingly. Because all firstborns and offspring of leaders (especially every year) is too much in itself and too biblical (as is the whole depicted picture). And the point here is not about the collective or crowd, but about the impracticality (every year without particularly valid reasons).

The goal of the quote is to confirm the fact of the sacrifice through an alternative source … the author of the treatise (a monk?) describes this from the perspective of the time after the arrival of St. Patrick … monks could of course distort, but it’s unlikely they invented it.

As for the details, they seem quite plausible to me; I would rather not believe in sacrifices in exceptional cases because in such cases it should not be a sacrifice but rather self-sacrifice. In cases of regular sacrifices, society perceives it at the level of the expected, not exceeding its limits. It’s important to understand that those who were sacrificed were not punished; rather, they were privileged, and a worthy death was considered by the Celts to be more honorable than a disgraceful life.

Therion, the question was not about the purpose of your citation, but about the purpose of the treatise itself, as the didactic works of monks aim to discredit pagan past and glorify the present, new way of life. They may have been written several generations after the events described when the people’s memory was distorted. Accordingly, significant inaccuracies cannot be ruled out.

As for the regularity of mass sacrifices, this is still not Mexico with its constant earthquakes needing ongoing pacification of the Gods. And it’s unlikely that there were enough people for periodic mass sacrifices. Regarding child sacrifices— for the clan (kin) this was always an exceptional self-sacrifice, not a mundane act.

I wouldn’t put it that way; each author certainly had their own goal, but for this topic, it is completely unimportant. Two independent sources confirm the fact of the practice of sacrifices, that’s all.

As for the form, quantity, and other details, we can debate for a long time, but how it actually was, we will not know.

I actually expressed myself not in support of what was written by a “monk” or Romans … it’s just easy for me to “imagine” this, not because I think the Celts were bloodthirsty or barbarians, but because their views on life and death are quite serious different from modern ones, and I also mentioned the differences in public consciousness … thus, all this together makes such a thing possible … in my opinion.

So let’s set aside prejudice and consider the quote … it mentions that once a year before Samhain, sacrifices were made in the temple on behalf of the entire people. Samhain is a threshold time, a portal to the other world … the “victims” transition to another world at the most convenient moment for this. Why? I dismiss the version of appeasement; pagans were not servile worshippers … I think the answer can be found in their mythology, where the bright gods frequently visit the domain of the dark ones, from which they derive considerable benefit; that is, firstly, and secondly, we often find in mythology cases of mutually beneficial (but more advantageous for the bright ones) exchanges between dark and bright forces. Based on this, we can suppose that the goal was to obtain knowledge and power, as well as to gain support, protection, and aid from the other side.

It seems to me that the meaning lies elsewhere.

Firstly, at the moment of death, the gates between worlds open, and one can “shout” through them what otherwise risks being unheard;

And secondly, and perhaps more importantly, at the moment of sacrifice, life and death swap places, and the death of one ensures the life of the others.

Exactly, the second looks like an exchange … the thing is that the artificially implanted humanism by the Romans hinders viewing this without prejudice … although in modern society such actions would be nonsense, besides the sacrifice, communal consciousness is also necessary, with clear representations from each member about the boundaries of the community, their role in it, and the place of others …

And regarding “shouting” … there is a contradiction here; if at the moment of death a passage appears to another world, then why arrange a ritual during threshold time when worlds are already intersecting?

“Because during the threshold time, power moves from the spiritual realm (нав) to the material realm (явь), while the sacrifice moves from the material realm (явь) to the spiritual realm (нав).”

Those sacrificed to Odin were hanged on the tree, one of the many heights of Odin –

Hangatyr

“the god of the hanged,” “Tyr (god) of the hanged”; to Thor, human sacrifices were also offered, and the chosen victim would have their spine broken on a stone.