Sigils and Tamgas

We have already discussed the so-called “True Name” of any being, regardless of the degree of its freedom and level of materiality, reflects the being’s individual energetic traits, or more precisely, represents the transformation of this being’s individual Logos becoming its vortex. In other words, the Name is the being’s “vortex map,” the path and mode of its manifestation, which is summed up in the well-known maxim: “nomen est numen,” “the name is the essence.”

Most often, when people speak of the “Magic of Names,” they mean controlling spirits, beings, and entities that have no physical bodies. However, for incarnate beings too, the Name is just as important a form of their existence, one of the levels of their manifestation. The ancient Egyptians considered the Name (Ren) one of the “souls” of a person, understanding “soul” as an energetic structure. In general, the ancients treated their names far more carefully than people in modern times: almost everyone had “secret,” sacred names under which they were known to the gods and to Power.

And if these sacred names revealing a person’s essence remained secret, not disclosed even to the closest relatives (except, perhaps, the mother), then “external” names, as expressions of a person’s influence on the world and their manifested activity, on the contrary, were proclaimed and inscribed. Those same Egyptians said that a person’s souls exist as long as their name is remembered, and therefore names were carved in stone, trying to preserve and protect them (royal names were even guarded by divine powers, placing them in cartouches).

Understanding that a name is not merely a designation, but a form of activity and presence, a person’s influence (and power) in the world, people since ancient times have imprinted their names in symbolic forms. Such a form of an “incarnated” name made it more tangible, and therefore gave it a greater power of manifestation.

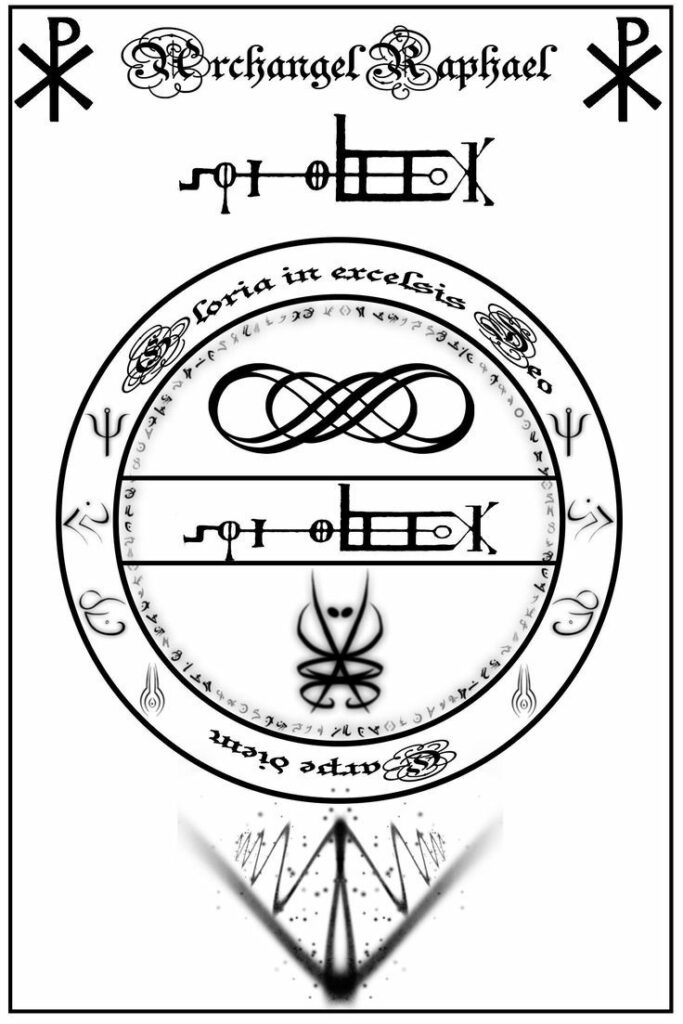

Just as the names of gods, angels, and demons were “woven” into a more energy-rich (and therefore easier to work with, and in some cases even for control) form than a simple written record — the form of a sigil — so too “powerful,” authoritative human names were symbolized by “individual seals,” the most ancient of which are the so-called tamgas.

A tamga is a symbol or sign historically used by tribes and clans in Central Asia, as well as by rulers of various states and empires.

The word “tamga” literally means “stamp” or “seal” in Mongolian and Turkic languages. These emblematic symbols were used by various Mongolian tribes and clans to denote membership in a particular clan or tribe. Tamgas were also used as official stamps and seals in the late medieval Turko-Mongol states and retained their importance in the early modern Islamic empires, such as the Ottoman Empire and the Mughal Empire.

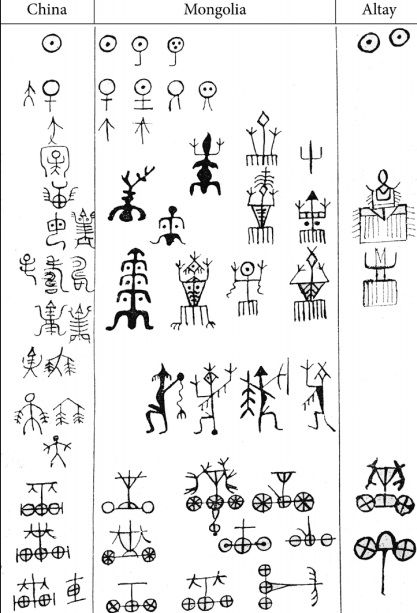

The origin of tamgas can be traced back to pictograms — the most ancient form of writing, in which symbols are images that directly reflect the essence of an object or an idea. Pictograms were used in various ancient cultures, including Egyptian, Sumerian, and Maya. Tamgas can be viewed as an evolution of pictograms, since they too are graphic symbols that can express ideas or designate certain objects and concepts.

Tamgas emerged in prehistoric times, but their exact use and development over time cannot be traced with precision. Numerous symbols in rock art are known that can be called tamgas or that are very similar to tamgas. They also often served to identify the presence of people in a particular place.

The origin of tamgas may be indicated through the simplest geometric figures (circle, square, triangle, angle, etc.), sacred pictograms, images of birds and animals, household objects, tools, weapons, and horse harness, and sometimes even letters of various alphabets. Totemic animals or other symbols connected with clan and tribal relations could have served as prototypes for many signs. Such pictograms went through stylization, which was necessary when applying a sign to a chosen surface with a heavy tool (chisel, knife, adze, etc.). The main requirements for a tamga-like sign were graphic expressiveness and conciseness, as well as the potential possibility of variation within an existing visual scheme. Thus, perhaps it was taken into account that using a sign would be easier if its outline were simpler since it needed to be applied to various surfaces (stone, leather, wood, etc.).

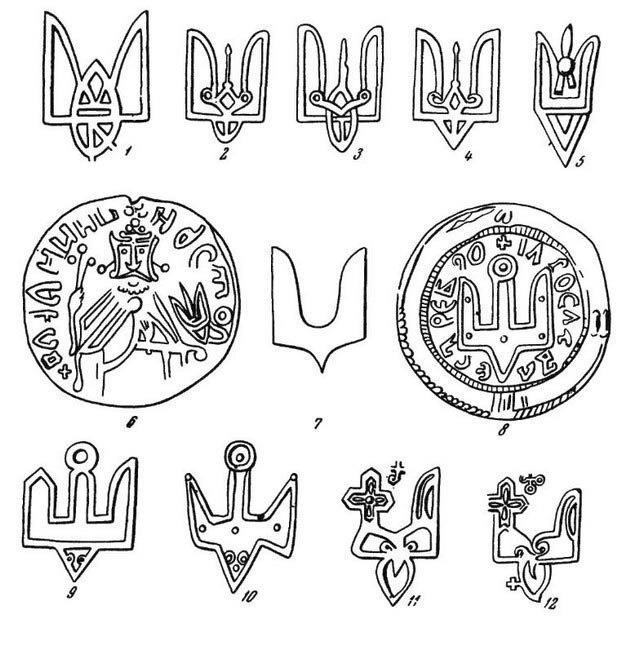

During the early Middle Ages, in Kyivan Rus, the princes of the Rurikid dynasty used symbols resembling tamgas to mark property rights to various items. In the East Slavic languages, the term “tamga” has been preserved in the state institution of the border customs office with an associated cluster of terms: to clear through customs (to pay customs duties), customs, customs officer (derived from the use of a tamga as a state identification).

An important feature of tamgas is the hereditary nature of their development. For example, the “coats of arms” of the princes of Kyivan Rus were personal symbols not passed on to descendants, and, like the symbols of the Bosporan Kingdom, had one base in the form of a bident, to which each ruler added (or removed) elements in the form of various “offshoots,” curls, etc.

Thus, tamgas acquired a connection not only with a single ruler but with a lineage or a state, embodying not only personal power but also the vortex of the physiological egregor, and later also becoming a support for national vortices, giving rise to coats of arms and state emblems. A vivid example of such an evolution is the tamga of the Giray lineage — the Crimean Tatar khans — which became a symbol of this people’s national identity.

It can be said that tamgas took on the function of supports for any human vortices — individual, clan, or broadly social — serving as the prototype of identification symbolism in general.

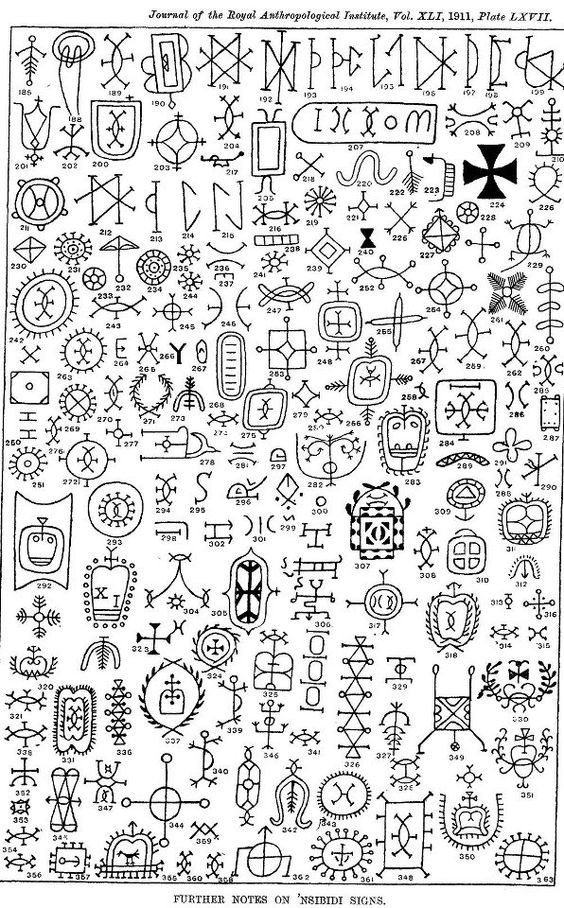

Like sigils, tamgas are graphic symbols used for identification and confirming authority. Tamgas are usually geometric or abstract symbols, while sigils may be more complex and detailed, including images of coats of arms, animals, plants, and other elements. Tamgas, like sigils, were often used on coins, seals, coats of arms, amulets, and in magical rituals.

In some cases, sigils could be used together with tamgas, especially in the context of diplomatic relations and intercultural exchange. For example, Russian tsars used named tugras (similar to tamgas) to seal charters and messages to the rulers of the Muslim East, which points to mutual influence and a similar application of these symbols.

Tugras can generally be regarded as the closest “worldly” analogue of sigils. This is a ruler’s personal sign (sultan, caliph, khan) in the Ottoman Empire, containing his name and title. Since the time of Ulu Bey Orhan I, who used the imprint of his palm dipped in ink to sign documents, it became customary to surround the sultan’s signature with an image of his title and his father’s title, combining all the words in a special calligraphic style, creating a faint resemblance to a palm. Tugras were widely used on state documents, coins, and mosque gates, performing an identification function, linking the manifestations of the monarch’s power with his personality, thus establishing a connection between the vortex and material levels of his activity.

Thus, tamgas are unique and multifunctional symbolic images used over the centuries by various cultures and states, that have undergone a complex and multifaceted evolution from an individual pictogram to (often) a nationwide emblem. Similar to how sigils express and embody the individual (and group) features of vortex beings, tamgas render visually people’s and societies’ vortex features, making them intuitively comprehensible, and also contributing to their anchoring and manifestation in the material world.

Hello! So, in other words, the older the symbols and the more personal power was invested in them by each individual representative, the stronger the tamgas affect the material reality? Unlike the forces invoked by runes, these are collective energy formations?

A tamga is a support for personal Authority. However, such Authority is most often understood and applied in a relatively simple, social sense. But if the personal power of the author of the tamga is sufficiently great or his social position and egregoric support are high enough, the tamga transforms into a real realization symbol capable of changing reality by the sickle mechanism. So, here the “antiquity” of the symbol has only an indirect meaning – only to the extent of how much energy supports the tamga, how many followers of the tamga’s author reinforce it with their power. For a mage, it might be useful to create such symbols, but one must remember that any capturing of energy is at the same time a support and a limitation, and what the final result will be, what will prevail – depends on many factors that are important to consider and “weigh.”