Alves, Zwerge, and Igwy

We have repeatedly discussed the clearest, most structured account of how various governing forces participate in the creation and maintenance of the formed universe developed by the Nordic myth. Because the Boundary is subtle in northern Europe, the ancient Scandinavians (as well as the Celts) saw much more clearly the role of each of the Divine Peoples in the world process than the Greeks of the classical era or even the wisest Egyptians.

That is precisely why it is most convenient to use Northern myth terminology when describing the origin and development of the forces of Prav and their descendants.

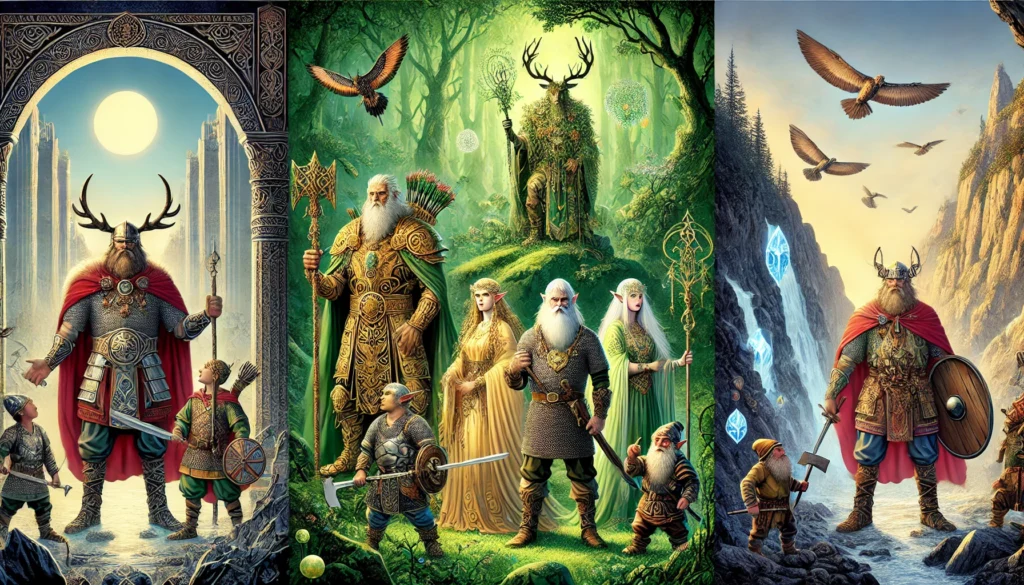

Accordingly, as we recall, this Myth says that four groups of forces participate in creating and maintaining the manifested worlds:

– Forces that “shape” the worlds “from outside,” acting “from top to bottom” — Aesir, gods of order and cosmic ordering;

– Forces acting in the worlds “from within,” sustaining life in them and the flow of energies — Vanir, gods of immanence;

– Forces that create the space of creation, selecting within the world-ocean of potentials those that are ready for realization — Ljossalfar, gods of possibilities and information;

– Forces that create points of support for creation and the unfolding of worlds — Svartalfar (or Dwarves) — gods of mastery.

We said that all these four groups of gods originate from the primordial creative forces that arise in the Medium as a potency of Manifestation itself — the Jotuns. At the same time, if the Aesir and Vanir are “direct” descendants of the Progenitors, then the origin of the Alves is more complex: Ljossalfar arise from the World of potencies almost “in parallel” with the Jotuns, being their “children” only formally, while the Dwarves arise “within” the Progenitors as the embodiment and manifestation of their own inner supports and structures.

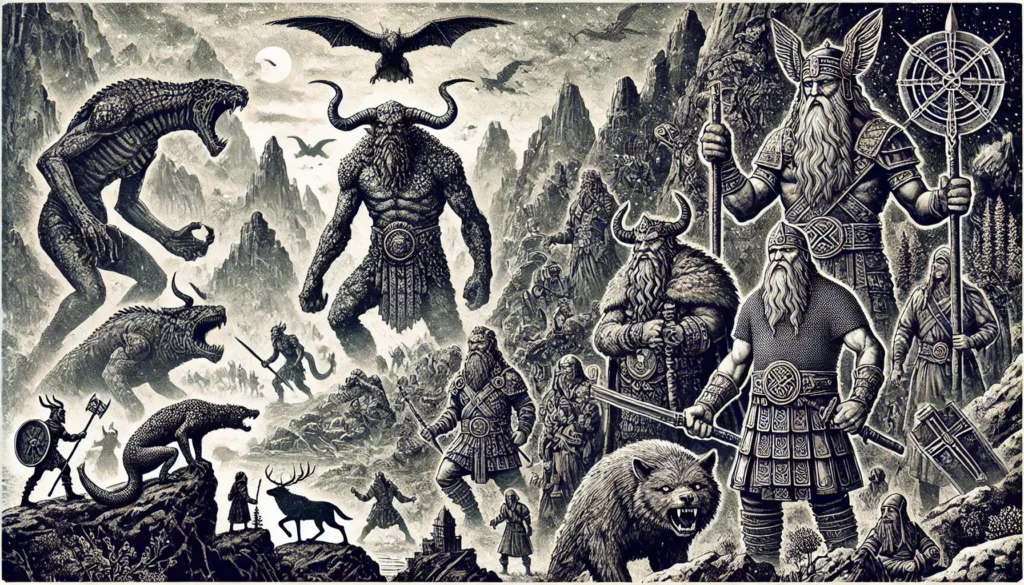

At the same time, the Nordic myth notes that the unfolding of the universe occurs in different streams: the “main” one realizes those potencies that do manifest in the lawful processes of manifestation (it is precisely this current that is described in most other mythologies as theo– and cosmogony), and “side” ones, which bring into play forces of resistance, inertia, or distortions that arise. In other words, alongside creation and development, degeneration and decay also occur.

And if most other cosmological systems immediately put these “side” processes outside the brackets, attributing them to the worlds of “darkness” or “evil,” the Nordic system pays more attention to them and indicates that before becoming real “evil” (that is, an obstacle to the development of the world), many groups of beings and forces follow a long nonlinear path, accompanied by the emergence of numerous “shadow” actors.

In this sense, the “main line” of the Northern European Myth carefully explores what, for many other systems, turns out to be their “apocryphal” or “esoteric” part.

From this point of view, it is important to note that although, in its “final” cross-section, the world can indeed be seen as bipolar — as a confrontation between the forces of creation and the forces of destruction — it is in the space between these two poles that the real world drama unfolds, where one cannot always clearly determine the evolutionary role of a particular group of beings or forces.

So, from this point of view, besides the fact that four mentioned groups of forces originate from the Jotuns, they also give rise to a large group of counter-creative forces — Hrimthurses, and then — Thurses, which, in turn, continue to “degenerate” into trolls and so on. We have already noted that the former can be compared with Archons, and the latter — with Fomorians and Nephilim of other mythological systems.

In a similar way, the younger divine peoples likewise produce forces that “continue” their work, but also tribes embodying built-up tension and destruction that accumulate in the course of their activity.

In this sense, the “direct” descendants of the Ljossalfar are the divine Sidhe, from whom, in turn, one of the largest faerie tribes originates — elves. At the same time, having mixed with the Fomorians or fallen under their influence, some of the Sidhe give rise to “Unseelie” faerie and dark elves (Dokkalfar). Likewise, having become “disappointed” in humanity, many Alves side with the Hrimthurses (Archons) or, at least, grow colder. In turn, other branches of the faerie people come from “giants” — thurses — and “fallen angels” — eliud. Thus, the faerie, in all their diversity, represent at the historical stage the “last” stage of the complex and multifaceted “side” development of the Gods of Space.

No less complex transformations the Svartalfar underwent as well. Strictly speaking, they manifested their divine nature only at the dawn of creation, while in the formed world they acted as forces producing “Higher artifacts” — objects necessary for maintaining the balance of the worlds under extreme conditions: Odin’s Spear and Ring, Thor’s Hammer, the chain restraining Fenrir, and so on. In this “craftsman” function, the Svartalfar are usually called “dwarves” (or “dvergar,” “dwarfs”), emphasizing their nature “under-manifested” from the Medium. In other words, when the gods need possibility, “space” for creation, they need the activity of the Ljossalfar, and when this creation needs to be “leaned on,” “supported” by something — the intervention of the dwarves is required.

However, this constant contact with the forces of shaping and transformation not only made the dwarves the main “masters” and “engineers” of the universe, it also “turned” them away from the spontaneous and living spirit; being in constant search for and creation of “external” supports, they gradually forgot internal supports; they began to replace creativity with craft, drifting further from free expression of spirit.

As a result of this process, most of the dwarves gave rise to yet another “degenerated” group — extreme “techies,” a people fully reliant on technology and scorning creativity (as an unpredictable and unregulated action) — igvas(or boggarts). The name “igvas” was first used by the mystic and visionary D. Andreev, who called this people of “degenerated” dwarves “devil-humanity,” emphasizing their falling away from the Great Flow of Power.

We have already mentioned that most encounters currently identified as “UFO contacts” are interactions with igvas, who cross the Boundary by technological means.

And if in more ancient times these beings were often confused with certain groups of faerie — most often with kobolds or boggarts — today they are often attributed an extraterrestrial origin.

In any case, it is important to understand that we are speaking of a high-tech civilization that developed in one of the worlds of our system — “Yggdrasil” — Svartalfheim, replacing and displacing its “original” inhabitants — the dwarves. In place of the small, harmonious, and exclusive settlements of the dwarves, high-tech igvas megacities appeared, and the art of making artifacts combining magic and technology, complementing one another, was almost lost. According to legends, somewhere in the expanses of that world small hidden dwarf settlements still remain there and even fortified citadels of svartalfar, but whether this is true is unknown.

Some of the dwarves who avoided technogenic degradation became refugees from their world, crossing into the Interworld and mixing with the faerie, and now, if the gods need skillful artifacts, they have to go not to Svartalfheim, but to look for solitary “smiths” in the Interval.

On the whole, apart from the general catastrophe, such a transformation of one of the worlds shows the fragile balance between creative and destructive forces and how easily greed, the spirit of possession, a progeny of the Dark Mother, can prevail even in one of the ancient and lofty spaces. And if Midgard’s humanity, having already experienced a division linked to dependence on technology, fails to learn from Svartalfheim’s fate, it risks repeating that fate in a more devastating form, and perhaps this scenario may be worse than self-destruction which, of course, is also quite likely for us.

Enmerkar, thank you for the article! I may ask a silly question, but still, why are elves depicted with characteristic ears? Does such an image of ears have any symbolic meaning, or is it an approximation to our perception of some ‘subtle’ aspects of these beings?

The traditional depiction of fairies with pointed ears is part of their perception as beings of the woods, close to nature spirits. Such ‘animal-like’ ears reflected the view that fairies, including elves, are part of the general ‘natural’ world while humans were perceived as separate from it.