What Did the World Lose When the Fae Departed?

The Great Departure of the fae was a macrocosmic event that changed the very principle governing the boundary between worlds. As long as threshold beings remained on Earth, alongside humans, the Threshold itself remained active — a fold in the fabric of reality, a point of connection and integration. It could be respected, appeased, bypassed, changed, guarded; one could make a mistake — and be stopped by those who know the requirements and costs of passage. But when by the 11th century the Departure was completed and the Threshold was left “unwatched,” protected only by the abstract power of the Guardians, the boundary ceased to be finely regulated. It grew “coarser,” darkened, became less “intelligent” and more mechanical.

From that time human history — especially European — entered a long period in which living guardians were replaced by surrogates: institutions instead of tradition, regulation instead of a natural balance, technology instead of craftsmanship, one-dimensional texts instead of the depth of the logos, fear instead of knowledge. The world seemed to lose those who knew how to preserve subtlety and poetry in it.

The first and most obvious consequence of the Departure was the final and irreversible technogenization of civilization and the increasingly consumerist attitude toward nature. While the fae were nearby, nature for humans remained not only a resource, but also an agent: the forest had its own will, every stone possessed memory, every stream had its own character.

This balance of forces manifested in the recognition that the world does not belong entirely to people: that it contains beings both older and younger, hosts and guests, places one should enter as one would a temple, not a warehouse.

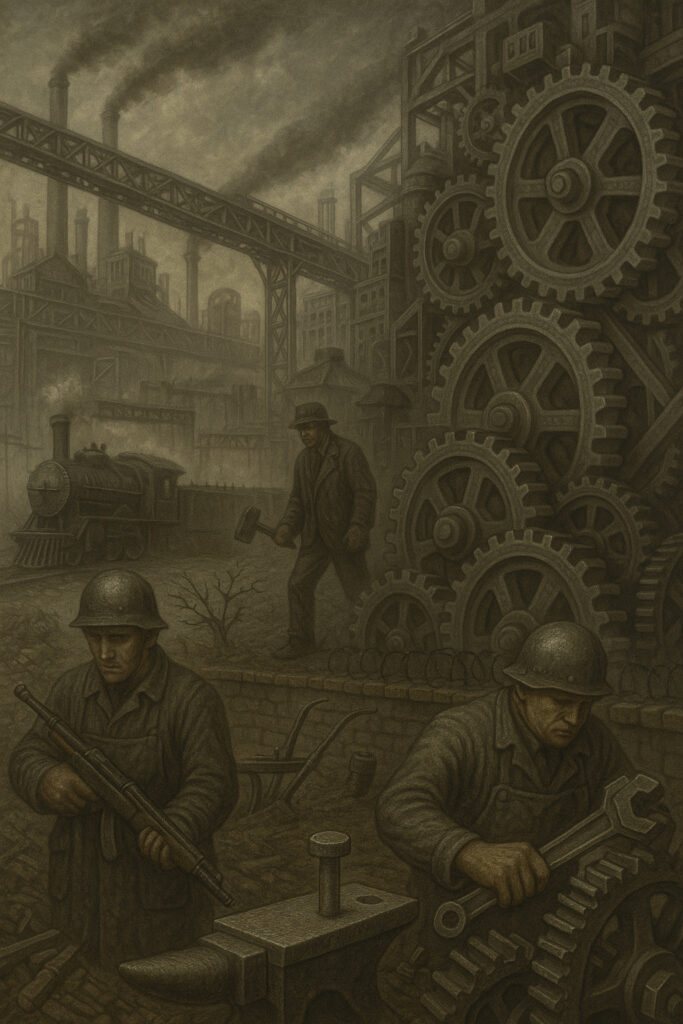

However, the departure deprived humanity of this constant, insistent reminder. And then iron, which used to be merely a material for tools — the plow, the sword, the nail — became a tool of violence. Automation, algorithmic thinking, and cold calculation increasingly prevailed in relationships among people and with nature. One could say that people began to live surrounded by iron, within a mechanism, within continuous “production,” and that nature in such a position inevitably becomes raw material.

With the departure of the Magical folk, the counterweight disappeared: threshold culture gave way to a culture of linearity. The forest ceased to be a magical kingdom full of forces and beings, and became a square on a map, a place of hunting and firewood harvesting. The river ceased to be a palace of nymphs and mermaids, and became merely a water resource. The land ceased to be the common body of the community, and became an object of private property, alienable and saleable. Threshold spaces — wastelands, forest edges, remote paths — began to disappear not only physically, but also legally: the world no longer needed “gray zones”; it required only a controlled “inside” and “outside,” a clear boundary of possessions, a transparent scheme of use. Thus came the era of enclosure of the world — a universe where everything is named, accounted for, measured, appropriated; and what does not fit is declared either wild, or empty, or dangerous.

The second consequence is the flourishing of witchcraft. Paradoxically, the less real Magic there is, the more its imitations appear. As mentioned, from a deeper perspective, Magic is not a set of “techniques” and not a collection of effects; it is a deep involvement in the cosmos, participation in the living structure of the world, the ability to interact with that which is older, deeper, and greater in scale than oneself, and to come out of it not destroyed but changed, having surpassed oneself. And for such an attitude, of course, threshold responsibility is needed, knowledge of measure is necessary, one needs an eye that can distinguish a door from a maw.

But when the bearers of living Magic leave, only practices without context and symbols without foundation remain. Then “witchcraft” begins, initially as a social necessity: people still need healing, assistance with childbirth, burial, protection from night terrors, the evil eye, livestock diseases, anxieties, and neuroses. And then those who can in some way work with the “subtle world” begin to be valued — herbalists, folk healers, enchanters, masters of “dark forces.” Such a surge could have become the basis of a new tradition if those able to hold the Threshold had remained nearby. Yet without oversight of the boundary, such practices very easily fall under the sway of dark forces, simply because the Threshold has degraded while predators remain as insatiable as ever. Where living guards once stood, entities of another kind now increasingly prowl: demons, elementals, utukku — all those who exploit “uncontrolled access” and derive benefit from it. In such an environment, witchcraft treads a very thin line: it both helps and entangles; it both heals and infects; it both protects and opens doors to those who should not be allowed passage.

Therefore, following the after folk magic flourished, hysteria of witch-hunts inevitably follows: society senses that dangerous contacts occur “below,” and it chooses fear over study and restraint; instead of discernment — accusation. Thus fear becomes a new rite, and execution a surrogate for the banishment of unclean spirits. Thus the world, having lost its true keepers of the Threshold, attempts to defend itself by its usual means — brute force — but by doing so only deepens the rift between Power and Wisdom.

The third consequence is epidemics, and more broadly: the invasion of necro-energies into the fabric of the world. It is no coincidence that in legends plagues are called “Slua Marb,” “The Slaughter of the Dead”: an avalanche-like growth of mortality, when the world seems to suddenly recall its vulnerability. In other words, the plague of the 14th century is a consequence of the Threshold letting through what should not pass, and not in the proper manner. Necro-energies intensify, shadows grow bold, posthumous traces do not dissolve but accumulate, and mortality itself begins to generate new mortality. Later this tendency repeats in new forms: the “Spanish flu,” AIDS, other pandemic waves — these are phenomena of a global world where boundaries have been erased by politics, roads, and trade.

And here an important connection becomes apparent: as soon as the Threshold is left without proper oversight, any “unsealing” of the human world — whether opening of routes, mixing of peoples, acceleration of communications — becomes a metaphysical amplifier of destructive interventions. The world becomes a single highway on which not only ships and trains travel, but also shadows, fears, diseases, and epidemics of possession. Where before energy structures were supported locally and “processed” by local spirits and local order, now not only life but also death flows without control or regulation.

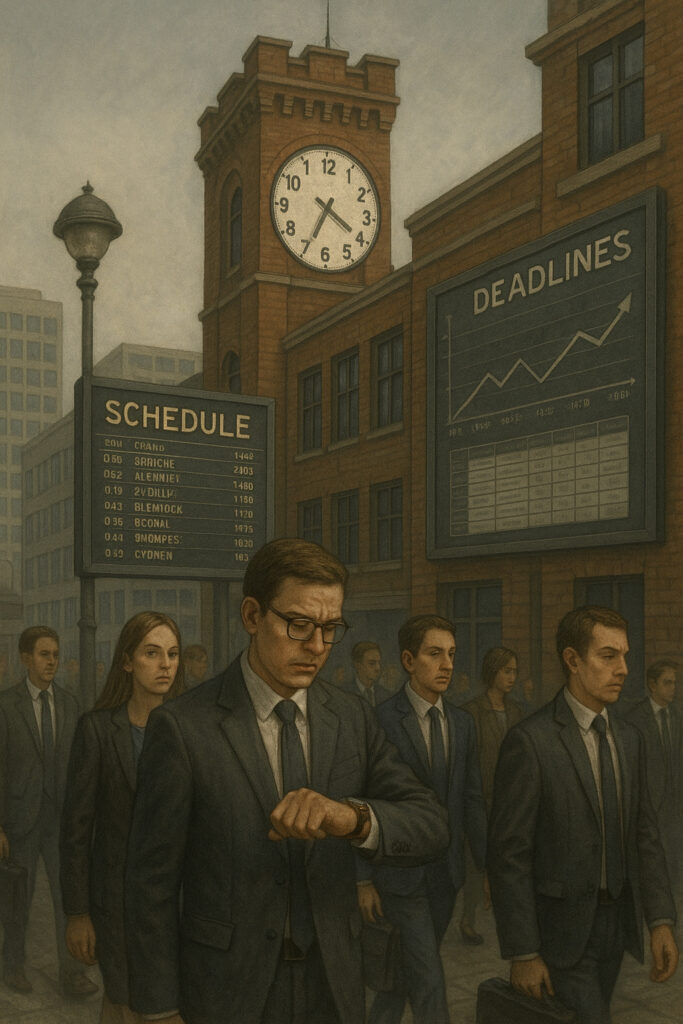

Thus, one can say that the Departure of the fae launched one great meta-historical process — linearization and regimentation of reality. The world moved from the calendar to the schedule, from cyclical time to a “digital” arrow. Time ceased to be an event and became a dimension. It became externalized — into the clock on the tower, into tables, into charts and deadlines.

Where time becomes external and the same for everyone, Threshold structures are seen as interference: bursts of spontaneity and unpredictability become a threat to the system.

Therefore, the system increases its pressure and imposes more structure. Everything that flows freely, flies, or burns is proclaimed “inefficient.” Everything that implies internal control is replaced by external standardization. Everything that rested on trust and the memory of clan, tribe, community is replaced by “impersonal” contracts and agreements, secured not by personal obligations but by an “external” seal. And especially important was the stage when the word itself became a commodity: printed texts give rise to a culture of “impersonal logos,” though at the same time they also unleash a surge of knowledge and open the path to grimoires, to “recipes” for gaining power without initiation.

Later, in the same vein, the scientific revolution arose: nature is finally described as a mechanism, amenable to measurement, disassembly and reassembly. And in this language it becomes simply impossible to speak to the forest as a spiritual entity; it can only be measured in cubic meters. And this is a direct consequence of the fact that there are no longer those in the world who preserved subtlety and prevented rigidity from stifling vitality.

In the social sphere, changes also occur: centralized state replaces the clan-based or feudal order as the main social instrument. And the state does what any structure not regulated by living keepers has always done: it tries to monopolize reality. It claims the exclusive right to decide which cults are permissible, which holidays are legitimate, which speeches are correct, and which knowledge is dangerous. It destroys local customs, ancient “agreements with the landscape,” which formerly protected people from the direct invasion of dark forces.

However, the stronger the state and the more rational its structure and logic — the more it depends on fear as an instrument of governance, because fear is a universal emotional “currency” that is easy to convert into obedience.

Thus begins the construction of new systems of suppression — scenarios in which freedom comes at too high a cost, where any way “upward” requires an exorbitant effort, and passive sliding down an inclined plane seems the only sensible course. And then the Threshold, Portals, and crossings become rare anomalies: flashes of freedom, escapes from the “matrix,” which are devalued, declared dreams or pathologies. It is no longer understood, no longer preserved or supported; it is feared or denied — and so energy is surrendered to those who dwell in darkness.

Finally, industrialization brings this historical tendency to its maximum. Iron becomes ubiquitous, noise — sound, light, and dust — becomes a constant background, high speeds become the norm; people cease to hear even their own breath, let alone listen to the murmuring of streams or rustling of leaves. Where once between humans and the world there remained “soft layers” — seasonal rites, sacrifices, mysteries — now machines hum ceaselessly and deafeningly. And at present these machine structures are being completed by digital reality; the world turns into an interface, attention — into an extractable resource, and the psyche — into a field of constant agitation. This is the natural result of the process begun by the Departure: when the Threshold was left unwatched, people began to learn to live as if there were no boundary at all, no depth, only a surface. However, this surface is not neutral: it becomes easier for those who prey on scattered, “smeared” energy to feed on it.

Therefore the Great Departure is not merely the “end of a fairy tale”; it is a radical transition from a world where the boundary was alive and inhabited to a world where the boundary became only a technical seam and a risk zone. Technogenization, witchcraft, and epidemics are direct consequences, followed by the disappearance of a culture of trust and the development of a culture of control; the disappearance of dialogue with the landscape and the creation of property rights over it; the disappearance of living continuity and the invasion of those who rejoice at any ownerless door.

Accordingly, today for a Magus the main task is to rebuild within oneself what was once supported by the presence of threshold beings: inner poetry, disciplined attention, respect for the boundary, the ability to discern forces and limits, and the ability to live in such a way that the world again becomes pliable and fluid where it has “hardened.”

How beautifully and deeply you have expressed it. Thank you.

Can it be said that Christianity in some sense served and continues to serve as a force for the ‘hermetization of the human world’ – a force that closes the Edge and indiscriminately labels everything supernatural, everything outside of this Edge as ‘unclean forces’? After all, there exists such a modern myth reflected in numerous books, movies, and series (a typical example being the series ‘Supernatural’), that for a long time there have been those who track any intrusions from the other side and destroy them – often without much discrimination, attaching the label of ‘evil, devilry’ to everything, the right to manifest in this world denied.

In the Middle Ages, many monasteries, on the contrary, attempted to take on the function of ‘mediators’ and control the Edge in the same way that it had previously been managed by the Enchanted People. This was especially noticeable in those regions where Celtic culture was still alive – in Ireland, Wales, Britain, and Brittany. There, monasteries often built in energetic nodes – at springs, groves, along the shores, and other ‘threshold’ places. In place of the fairy castles came monastic ‘islands’ – hermitages, cells on rocks, abbeys by the sea. This was, whether consciously or intuitively, an attempt to ‘place a new guard’ where fairy processions once traveled, to take on the role of intermediaries. In a sense, monasteries indeed acted as shields, protecting from the rampage of elementers, providing people with ritual discipline, ‘rules of transition’, comfort, and form in an era when the world was overflowing with death. But over time, of course, any shield risks becoming a solid cocoon, and monasteries turned from regulators of the Edge into its imprisoners. The Magical People gradually came to be branded as ‘charm’, ‘deception’, ‘unclean’, and part of what in ancient traditions was subtle and ambiguous was banned or displaced into superstition and fear. And so, what was meant to be a shield transformed from a wall against evil into a barrier against maturity.

It seems that people are placed in this reality, creating a semblance of an experimental platform, where unfavorable adaptive traits – a tendency towards violence, suppression, emotional deafness, a preference for suppression over learning and adaptation, etc. – gave an advantage in survival, but not in development. And when the experiment showed that these unfavorable traits can indeed develop, distorting the structure of reality, this platform was seemingly abandoned to rot naturally, to the delight of scavengers.

Thank you, very interesting.

I would also like to add that ‘destructive forces’ have long taken control of states and the entire management system of our so-called civilization.

They declared that ‘they’ do not exist.

They built a farm here. Reformatted, turned the consciousness of people into cattle…

Do you not think that when the system is dominated by a destructive element, it will collapse sooner or later? And everything is heading that way..