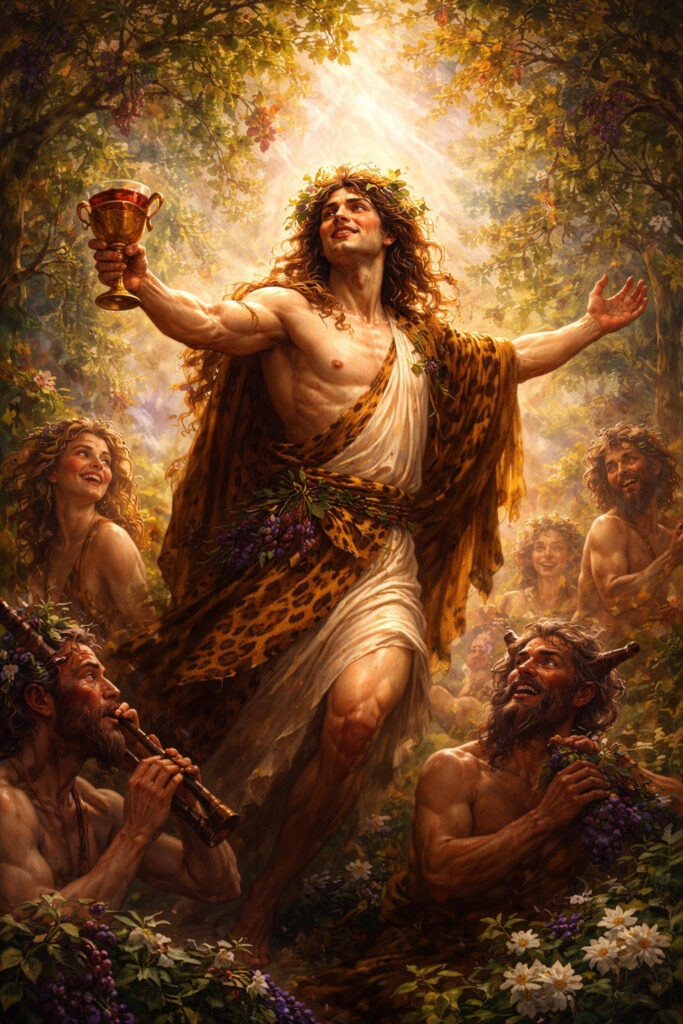

Dionysus and Beelzebub

The Dionysian principle is the living fabric of the elemental sphere of feeling as a mode of being in the world; it is what gives the stream of consciousness intensity, involvement and the capacity to experience reality as a living, immediate presence. In the classical account it was precisely that which made the soul tremble when the city-dweller grew weary of reason and prudence: the Dionysian brought enthusiasm (literally, “the indwelling of the divine”) — a restoration of the waning fullness of experience.

However, the Dionysian principle, although it makes life deep and beautiful, can just as easily “spill over” if the stream does not find a suitable vessel for itself, generating whole chains of destructors.

The most common mistake made when one over-emphasizes the Dionysian is to treat feelings as the opposite of cognition. In its original sense the elemental sphere of feeling is not the “opposite of reason” but the primary medium in which the impulse to seek gnosis is born. It is a primary intuitive recognition — a subtle inner discernment not yet formulated or articulated, but already capable of responding and giving an emotional sense of what is useful and what is harmful, what is true and what is false. This sphere is an instrument of initial orientation, a field of conscious potential in which the first shoots of future decisions, understandings and questions arise. Hence, when this sphere is distorted, not only “emotional life” is damaged: the very mechanism that moves consciousness toward knowledge is warped.

This is exactly how the ‘desire not-to-know’ destructor is born — Beelzebub, which can be seen as the “abyss” of Dionysus. The “Lord of the Flies” is not “the chaos of emotions,” but a special emotional ignorance — a refusal to do inner analytical work and discrimination, replacing cognitive activity with a rush to grab ready-made “wisdom” — preferably immediately and without risk, and in such a way that it confirms the mood already in place.

Beelzebub is an extraordinarily multifaceted demon who, although not among the goetic Gatekeepers, stands behind many of them, representing the basis on which other destructive matrices are formed. He embodies the very principle of demonic paralysis of the will, which, however, does not act at the level of potency (it belongs to the domain of the activity of Archons), but at the level of emotional-sensory motivation, at the level of the “fuel” of desires that sustains the fire of will.

This demon destroys the very structure of thinking and intuition, so that the mind ceases to distinguish inspiration from a whim, and the search for gnosis begins to seem boring, futile, and meaningless. He “extinguishes” the very desire for development, the striving to think, understand, experience, and attain insight.

In itself, the Dionysian principle enables the mind to feel reality holistically, in its full light and darkness, beauty and cruelty, and that is precisely why it can become a path to direct gnosis, because real truth is first lived through, and only then formulated.

However, the distortion of this primordial principle creates a deceptive ease where feeling ceases to be a conduit of depth and becomes a justification of superficiality.

Beelzebub is the destroyer of the blurring of the mind’s hierarchy, the mixing of emotions, ideas, desires, passions, and their interweaving with whims and caprices, which are declared to be “true desires” and therefore idealized and granted the status of an inner law.

This is how the ‘snatching ready-made wisdom’ destructor arises. It is clear that cognition, by its very nature, requires considerable time, effort, mental flexibility and readiness to doubt what has been “understood,” to revise images of the world and of oneself. Therefore the cognitive process tends to curb pride, forces one to admit gaps, see uncertainties, take steps into the darkness of the question.

And it is precisely the Dionysian stream that can give the strength to take risks, give courage to live through things without running away. Beelzebub, on the contrary, turns feelings into a mechanism of avoidance. Then, when an honest anxiety about not knowing arises in the mind (and following it — the labor of understanding), under the influence of the Lord of the Flies irritation arises from the very fact of complexity: “why do I need this?”, “this is boring,” “this takes too long,” “I already feel everything anyway.”

And then, instead of building the process of cognition, the mind begins to consume “wisdom” as a stimulus, as confirmation, consolation, a social marker of belonging to those “who understand.” A person who has fallen under the power of Beelzebub collects formulas, aphorisms, symbols, “keys,” but does not use them as steps in cognition, as supports of the cognitive process, and simply wears them like status amulets.

He mistakes knowledge — understanding causal relations — for the mere reproduction of congenial stories that simply flatter his mood. This is the “fly” drawn to filth: as we have already noted, Beelzebub is not the filth itself but the attraction to it — an emotionally charged and justified substitution for genuine cognitive activity.

At the same time, Beelzebub undermines not the intellect but the heart of cognition — that immediate gnosis which is rooted in feelings and is born from the first awakening of the conscious pole. And it is from this that Beelzebub isolates the psyche, slipping in, instead of an “inner compass,” a tangled ball of impulses.

That is why he so often becomes a “bridge” between different demonic matrices. When the element of feelings ceases to serve discrimination and turns merely into a set of caprices, the striving for gnosis very quickly turns into the desire to possess the best: not to be — but to have; to appropriate rather than understand; to seem to have arrived rather than go. And at this stage, the distortion of the Dionysian element turns out to be a direct obstacle to cognition, because any attempt at analysis is experienced as a threat to pleasure, any verification — as an insult, any complexity — as “violence against immediacy.” Thus the mind acquires a strange “emotional dogmatism”: it seems to live by feelings, but those feelings are not alive; they are turned into a system of prohibitions against reality.

In the case of the distortion of the Apollonian principle discussed earlier, the main problem is that the light of discrimination ceases to serve wholeness and becomes either a “scalpel without synthesis” (analysis that cuts until the whole disappears) or a prison of a single, supposedly correct description.

In the case of Beelzebub’s activity, the same enslavement occurs, but now in the “a single ‘correct’ mood,” and the destructive matrix creates the impression that mood equals truth. If the degradation of the Apollonian turns the world into a cold scheme, then the degradation of the Dionysian, on the contrary, turns the scheme into needless luxury, relying on a distorted “emotional intelligence”: “an impulse is enough for me,” “a sensation is enough for me,” “it is enough that I am outraged/inspired.” At the same time, both types of destruction lead to a refusal of real transformation: where intellectual (or emotional) labor is required — a simulation is created; where there should be a meeting with the field of perception — there appears a comfortable virtuality of emotions.

It is clear that Beelzebub often enters the mind as the result of a revolt against the Apollonian. When a person grows tired of parameters and definitions, of the discipline of discrimination, and of the fact that cognition requires effort, patience, testing, the admission of mistakes and sometimes a painful revision of one’s whole picture of the world, the psyche becomes vulnerable to the destructor’s influence.

The element of reason is always a thorny path to clarity: step by step one must distinguish the true from the false, the important from the illusory, facts from self-consolation. However, when this work takes on a negative emotional colouring — when it is experienced as pressure, shame, or “violence against spontaneity” — the psyche often responds with emotional resistance: “I will not think,” “I do not want to sort this out,” “I do not want to distinguish.” The power of the realm of feeling is not in rejecting reason but in giving it living motivation and depth.

And it is precisely then that Beelzebub implants a shield against the intellect; he promises not merely relief but an entire ideology of relief. He proclaims unwillingness to make an effort as a principled stance, and incompetence as “freedom.” And then feelings of fatigue and intellectual laziness are already presented as a virtue, as evidence of the “liveliness” and “naturalness” of mind, which is opposed to “cold rationalism.” It is very convenient to believe that since discrimination requires labor, then it is not needed; if competence does not come easily and pleasantly, then “it’s not for me.”

Thus Beelzebub erodes the demand for effort and opens the way for deeper Archontic influences that suppress cognitive activity, until the very distinction between knowledge and ignorance is no longer felt. Competence becomes suspect (“they show off”), while incompetence is celebrated (“I don’t overthink it”). The more the psyche avoids the discipline of thought, the more it needs to convince itself that avoidance is not weakness but “insight.” A vicious circle forms: refusal of logic breeds ever more false beliefs, and those false beliefs in turn demand ever stronger emotional self-justification.

As a result, the “revolt against Apollo” does not liberate Dionysus but only deprives thinking of meaning. The power of the element of feelings is not in rejecting reason, but in giving it living motivation and depth.

Under the influence of Beelzebub, instead of feelings functioning as an instrument of quick appraisal, they are erected into a mere shield against the intellect; instead of living involvement there is comfortable self-sufficiency; instead of the thorny path of cognition there is the reception of ready-made myths, simple answers, “deceptive gods,” and pseudo-explanations — all of which turn out to be false because they have not been lived through or tested.

Thus Beelzebub turns out to be the destructor of cognition through feelings, depriving the process of cognition of emotional reinforcement, making intellectual efforts “uninteresting,” destroying motivation for cognition. And if the motivational scheme is distorted, the flow of information turns into a flow of stimuli, and “knowledge” into an illusion of being informed without structuring and synthesis. And this opens the way to deep Archontic influences of suppressing cognitive activity, when the very distinction between knowledge and ignorance ceases even to be felt.

We have already discussed that “Beelzebub makes demons visible”; he is almost always included in a system where different destructors act at different levels of the same process — the derailment of the process of cognition.

At the same time, it is Beelzebub who “breaks the inner engine” of the cognitive process, while other destructors help either to consolidate the breakdown or to extract energetic benefit from it.

At the level of the Triad of stopping, a close connection arises between Beelzebub and Baal: refusal to know — with consent to a surrogate of knowledge. Beelzebub makes cognition emotionally unbearable: thinking is “boring,” sorting things out “pointless,” checking “humiliating,” and complexity is perceived as an insult. He deprives one of a “taste for truth” and replaces it with a taste for quick relief.

Thus a vicious structure of lazy consciousness forms, in which laziness becomes a source of demonic destructors and pseudo-explanations that can be accepted without labor and risk. Baal is the King of easily digestible lies: he makes lies practical, smooth, and emotionally profitable.

And while Baal fills the mind with surrogates of knowledge, the King of Wrath — Belial — turns this surrogate into social cement. When cognition is weakened, the mind compensates for its inner uncertainty with an external support: a group, a circle where uncomfortable questions are not asked and a sense of community is provided. And if doubts suddenly arise, Belial activates shame and threat: “don’t break the unity,” “don’t air dirty laundry,” “don’t show off,” “be like everyone.” And then, just as Beelzebub removes the inner criterion of truth, Belial replaces it with an external criterion of loyalty.

He can either be rejected, incurring the vengeance of the repressed god, or he can be accepted and contained, restoring hierarchy within the stream of feelings so that it becomes a fertile vineyard rather than an impassable forest thicket. Lilit is a distortion of the very capacity for living connection, which produces ignorance as a refusal to love (in the sense of acknowledging the other’s otherness and freedom). Dionysian unity at the level of Lilit is distorted into possession, when “to unite” means to appropriate, dissolve, absorb, make “mine.”

That is why Lilit is often named both “mother” and “spouse” of Beelzebub. She turns emotional laziness and capriciousness into greed and consumption, because when there is no discrimination and responsibility, intimacy also manifests only as possession. Both destructors reject process, work, effort: Beelzebub — in the process of cognition, Lilit — in the process of mature love (as a combination of freedom and mutuality). The first destructor makes mind lazy and self-satisfied; the other — greedy and devouring.

Thus a vicious structure of the lazy mind is formed, in which laziness becomes a source of demonic destructors. Beelzebub switches off motivation for cognition, turns complexity into an irritant; Baal slips in “ready-made wisdom” that is easy to swallow and pleasant to have; and Belial turns lies into a collective identity and forbids doubt as betrayal. Lilit expands the refusal of cognition into a refusal of genuine love and freedom, turning the entire path of mind into a hunt for appropriating knowledge, experiences, states, powers, “initiations,” people.

In this sense, Dionysus grants the ability to experience truth as presence and to live it as a path. Beelzebub, however, makes the mind content with ignorance, and that contentment begins to seem like spirituality.

Accordingly, the most effective resistance to the “abyss of Dionysus” — as well as to the “abyss of Apollo” — is the Orphic synthesis. It is clear that Dionysus cannot be “defeated” — just as life itself cannot be defeated. He can either be rejected and one receives the vengeance of the repressed god, or he can be accepted and contained, restoring hierarchy within the stream of feelings so that it becomes a fertile vineyard rather than an impassable forest thicket. And this means that resisting Beelzebub consists in returning self-identification and self-analysis, preventing desires from being replaced by whims, returning the stream to its sources, so the river becomes a clean current, and not a succession of puddles over which flies circle.

Thank you, excellent article!

Mmm…what a …nutritious article.. bravo to the author)). There is much to ponder and digest. )) Glad I came across these pages. Thank you very much.

Thank you very much.