Batin and the Priestly Estate

As soon as a person enters some “closed circle” — becomes a monk, a priest, a member of an Order, and so on — an obsessive desire arises in them to “hide” and “guard” the access they gained to the divine, to wisdom, to place themselves between the Higher and the lower. In reality, this is often not a striving to truly protect the sacred from profanes, but a desire to appropriate God, to become his “sole steward,” deciding who is “worthy of salvation,” one of the forms of the destructive force of possession, inspired by the King of greed — Asmodeus.

This manifestation of distorted force of attraction, leading to “monopolizing spirituality” and obstructing the expansion of the ascending current of consciousness, is known under the name of the Wise Batin — a demon of secret societies and priestly estates.

The demon’s name is associated with the notion of “secret knowledge”: in Muslim theology, this was the name given to the “inner,” hidden meaning of Scripture, as distinct from the external, literal level (zahir). Over time, this term turned from a concept of hermeneutics into the proper name of a goetic gatekeeper, embodying that shadow which almost inevitably arises where there is a distinction between “zahir” and “batin,” between the open and the secret.

As long as this distinction serves to deepen understanding and expand the mind, there is nothing destructive in it. The human mind truly thirsts for mystery: people want not only to know texts and ideas, but to understand what stands behind them; not only to perform rituals, but to experience their inner meaning.

In this form, this striving is personified by the solar Genius Kaliel, “God who hears swiftly,” opening to the seeker that “secret of the Lord which is revealed to those who fear Him,” that is, the power of direct insight, a flash of understanding irreducible either to the letter of texts or to others’ authority.

However, when the experience of involvement with a mystery turns out to be not an engine of development, not a striving to “bring the Light,” but a foundation for a feeling of superiority, the matrix of Batin activates in the mind.

This destraktor manifests as a striving to identify the idea of depth with oneself, turning it into property. The striving to see the roots of being, to live at the sources of meanings, under Batin’s influence turns into “artificial depth” (bath — Bath): a cozy personal space where the mind steadily admires its own “wisdom,” “revelations,” and jealously prevents them from flowing into the outer world.

In the Kabbalistic interpretation, this state is described as בעט — being ‘in one’s head,’ in the cycle of inner associations, comfort, and self-soothing. The task of the path is to turn this private depth into a vessel, כלי: to preserve the capacity to experience depth, but to make it a container for compassion rather than a pretext for self-satisfaction. In other words, Batin’s energy requires a transformation from “warm self-enclosure” into a form of participation in the world, where depth is tested by fruits, not by the feeling of comfort it evokes.

Batin is also a demon of contrived and egocentric regularity: he provokes the mind to “see signs” everywhere, to elevate random coincidences and childish fantasies to the rank of a “secret doctrine,” which only reinforces the feeling of chosenness and self-satisfaction. Invented connections seem to him more reliable than reality: fictional “mahatmas,” “ascended masters,” “ancient orders,” and “primordial traditions” turn out to be far more convenient than living contact, because they do not require verification, do not challenge, and do not disappoint. Thus a perceptual error — apophenia — is elevated to the rank of a source of “wisdom” and begins to reinforce the destraktor, dissipating enormous volumes of energy both of its bearer and those who believed him.

The sigil of Batin illustrates his nature well. In one of its readings, one can see a herald with a trumpet and a banner fluttering behind his back — an image of one who not only “knows the secret,” but is obliged to proclaim and impose it as an object of universal faith. In another, the outlines of winged bulls-shedu can be guessed, guarding the entrances to Assyrian temples: guardians of thresholds, protecting the sacred from “outsiders.” Both images share one function: Batin is not only the enjoyment of one’s chosenness, it is also the need to turn chosenness into a commodity for others, to build a teaching, a school, an order around oneself, where he himself will be the steward of access. A priest, monk, initiate who falls under the power of the Wise Duke strives to build the “most beautiful” temple, monastery, lodge, but at the same time to close its doors, in order to arouse envy in the “uninitiated” and thereby increase his own significance.

It is no accident that the Lemegeton speaks of him as a ruler who knows the properties of herbs and stones and is able to instantly transfer people “from one country to another.” On the level of the psyche, this means two of his most important tools. First, he really has access to some hidden patterns of the world — understands how something works, but this partial truth fuels pride: “since I know what others do not understand, I am far above them.” Second, he provokes the mind to irresponsibly jump between levels, to declare equal things that cannot be compared: the physical and the spiritual, a personal feeling and an absolute law, one’s insight and the “will of God.” Where everything is equalized, any personal experience can be declared a revelation, and any disagreement with it — ignorance or heresy. This is the ultimate form of apophenia, when “everything is connected with everything,” but these connections are built not according to real gravitations, but only according to the need to “fit the world” under an already ready-made idea.

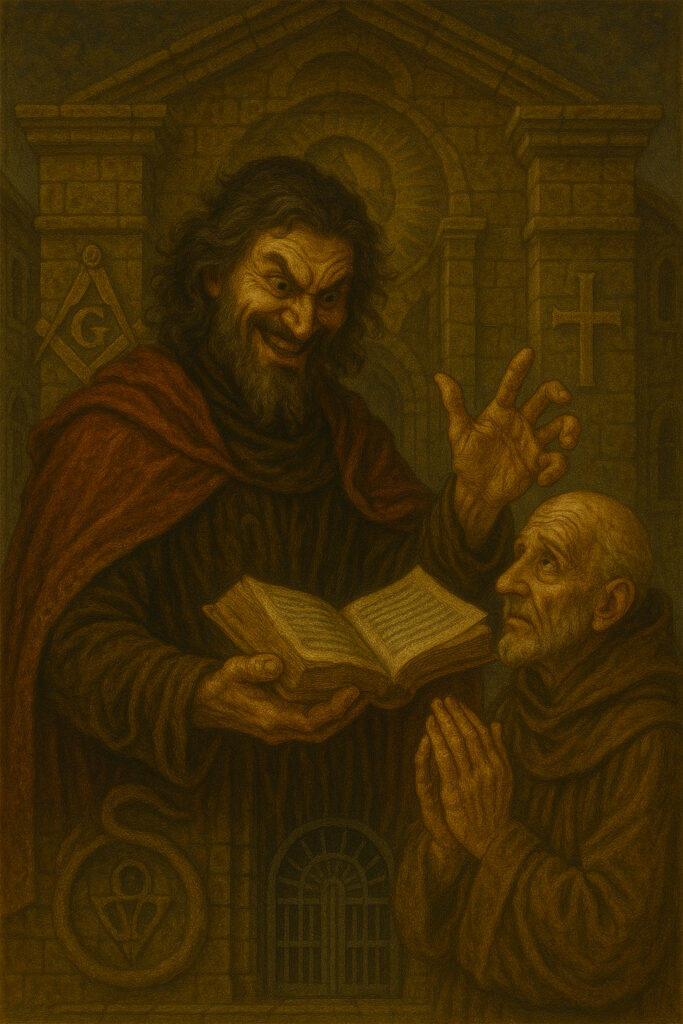

This matrix could have remained a private problem of esotericists with overactive imaginations if not for Asmodeus’s inspirations: for a person living under Batin’s influence, it is not enough to enjoy their own “secret depth,” they need witnesses. Inner intoxication with chosenness is not enough — a flock, students, or at least an audience is needed, a circle of those who recognize his “special status.” In this sense, Batin fulfills his main social function: he builds a priestly estate.

Any closed circle — a monastery, the clergy, an Order — is by definition separated from the world. To enter it, a person always makes a sacrifice: gives up some external opportunities, personal life, a solid career, or a family future. This sacrifice is often sincere: behind it stands a genuine striving for development, for meaning, for service. However, the higher the “cost” of entry, the more painful it is then to admit that “outside” people can have an equally direct contact with the Divine. If any layperson is able to pray, contemplate, love, and see as well as a monk, if anyone can hear God as deeply as an initiate — the priestly sacrifice risks seeming excessive.

In order not to face this inner question, the psyche almost automatically builds a defensive construct: since I am “inside,” it means there is something here that “outside” does not have and cannot have. A special grace, initiation, a “true tradition,” a correct line of succession, a faithful interpretation. This is how Batin is born as a destraktor: the living feeling of vocation is replaced by the idea of exclusive access. The feeling that “I, of my own free will, gave much for the sake of seeking God” is replaced by the idea that “God can be accessible, truly, only here, through me.”

In this form, care for the sacred turns into the striving to “guard the shrine from outsiders.” The words still look pious; they speak of the “fragility” of the mystery, of the need to “protect the secret,” that “one must not cast pearls before swine.” And all of this, of course, is so — but only until the “gatekeeper” turns into a “guard,” until he appropriates the right of passage to the Spirit, until he forgets that he is only a minister, not a steward. Unfortunately, rather quickly fear becomes not a fear of profaning mysteries, but a concern for one’s own position: if one admits that the holy can act also outside the “walls of the monastery,” that grace is not rigidly tied to ranks and initiations, that the pass to God (Buddha, Spirit, Power) is issued only by the seeker’s own mind — the role of the priest ceases to be a monopoly. Then service remains, but privilege disappears.

That is precisely how Batin grows from a “private” demon of esotericists into the “reverse side” of the priestly estate. A priest, monk, member of an Order infected with this matrix ceases to be a witness and a guide and becomes a steward: he does not simply serve at the Gates, but declares himself their owner. Access to Power turns into a service, salvation into a scarce resource, distributed “at the discretion” of those who stand at the altar.

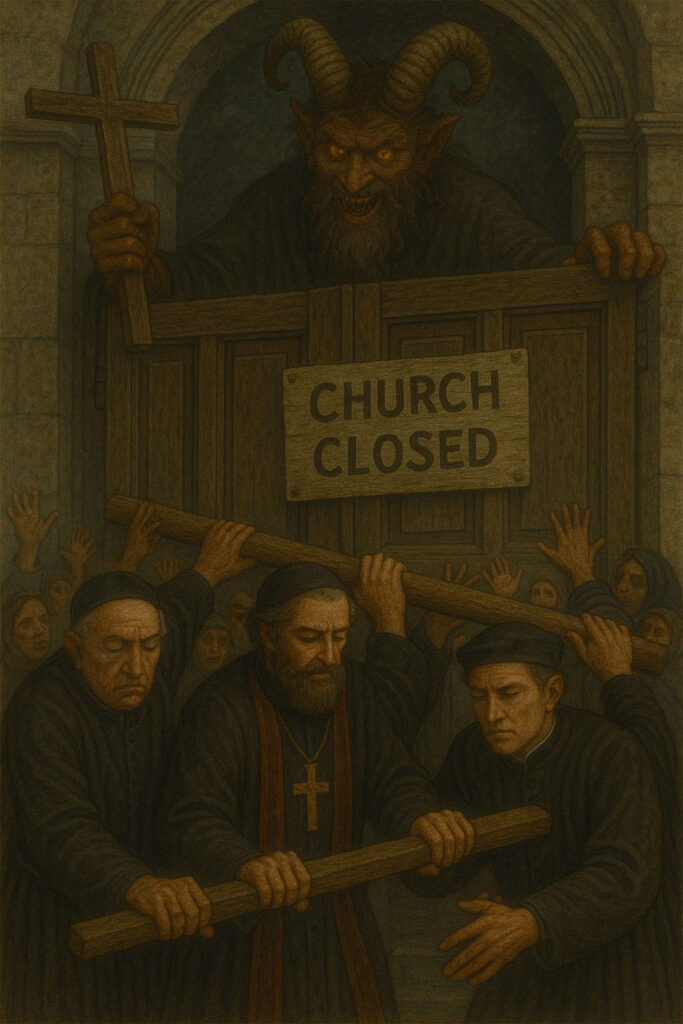

Thus, Batin, being a form or a younger aspect of the King of possessiveness, spreads his principle to the relationship “human — Power.” Then, just as Asmodeus turns a partner into an object of possession, Batin turns God Himself into an object of possession. This manifests in many small distortions of the mind which outwardly look like piety, but in essence are an attempt to monopolize the right to the sacred. Church, monastery, Order, school, teacher, tradition — all of this normally should be an environment in which a person learns to surpass oneself. However, under Batin’s influence, a natural boundary becomes a raised fence, and belonging to the “inner circle” becomes a way of “exclusion.” The Most High God turns out to be “our God,” Buddha — “our Buddha,” belonging to the group — the only guarantee of “correct” contact, and those who are outside are automatically devalued as “uninformed,” “immature,” “deceived.”

Thus Asmodeus’s matrix becomes entrenched in the spiritual sphere: “because we give you salvation, you must pay with obedience, loyalty, resources.” The marriage of a human with God is replaced by the marriage of a human with an institution, and the institution already, on its own behalf, decides whether someone is “worthy” to go further. And it is precisely Batin who considers himself entitled to decide for others what is “within their power,” what is “forbidden” to them, what they are “ready” for.

Within closed spiritual structures, such a notion quickly becomes the norm. Batin carefully slips in explanations: “we do not appropriate Power, we only ‘protect’ it from those who ‘won’t understand’; we do not close the road, we ‘save’ souls from dangerous experience; we are not dependent on the flock’s recognition, we ‘give them responsibility for salvation.’”

However, if one goes behind these verbal shells, it remains to honestly admit that very often God has been turned into a resource assigned to a specific institution; in other words, Batin inevitably enters Asmodeus’s retinue — the desire to possess — as the desire to declare one’s possession the only legitimate one.

Carriers of Batin’s matrix in fact invert their original task: instead of guides to Power who help a novice pass safely, they turn into blockers of the path; they do not lead to power and enlightenment, but close (or complicate) access to them. And although formally they “serve” the path, grace, tradition, in essence they usurp the place of the Gates — so that the seeker encounters not the living Source, but a system of filters, checks, and permissions. Where a priest, monk, initiate should have become a mystagogue, the bearer of Batin becomes an arrogant obstacle. He is not a model to emulate but rather, on the contrary, an example of what a true Wayfarer must not be. The thought that “if I practice this system, I will turn into the same self-satisfied fool” is repelling and becomes a serious obstacle for a sincere seeker. And the presence of such a “priest” not only does not ease the path, it lengthens it, turning the road to Power into a labyrinth built around someone else’s need for significance.

At the same time, this matrix is easily activated within the seeker. At a certain moment, an inner “little priest” appears, who decides which movements of the soul are “permissible” and which are “unclean,” which thoughts are allowed and which must be declared “the enemy’s thoughts.” This is not conscience, not a daimon, and nor sober discernment; it is an inner overseer who always stands above and never answers. However, true spirituality presupposes risk: the risk of making a mistake, revising past experience, admitting illusions. Batin levels this risk. He gives birth to an inner prohibition on testing one’s own “revelations” by the fruits of life. A person begins to hide their experiences not from “profanes,” but from reality itself, which could show that half of the “secrets” on which their identity is built are merely apophenia, inflated by vanity.

Accordingly, resistance to Batin begins with the striving to step out of the warm bath of artificial depth and become a real vessel in which depth is commensurate with the world. The only reliable criterion that allows one to distinguish genuine deepening from the influence of the Wise Duke was already proclaimed in the Gospel: “by their fruits you shall know them.” Not by the number of levels of interpretation, not by the number of initiations, and not by “great revelations,” but by what happens to life — one’s own and others’. Where “secrets” make life narrower and scarier, bring more dependence, more guilt, and less freedom — Batin is active. Where depth simultaneously increases clarity, responsibility, compassion, and the capacity to love — Kaliel is active.

The priestly estate, as an external and internal institution, is absolutely necessary and will exist until people learn to take full responsibility for their own spiritual life. However, Asmodeus and Batin know how to settle both in monasteries and even in orgies, in scientific schools, and in “enlightened” communities. Therefore, one should see in any form of service not a way of possession but a form of support; not a monopoly but a kind of compassion that is appropriate then (and only for as long) as the seeker has not yet learned to rely on themselves.

Batin awakens in the mind every time we gain access to something greater — to knowledge, to power, to others’ trust. At this moment, a temptation arises in the mind to hide it, secure it, make it “my precious,” to declare oneself the sole keeper of the Gates. And each time the question must arise: do I really protect what is fragile — or am I hiding what I myself do not yet know how to handle with integrity? The answer to it determines who rules in this place: the Duke of “hidden knowledge” or the mind itself — and not to try to appropriate what by its nature cannot belong to anyone.

Enmerkar, what a deep and relevant article. It penetrates right into the soul. And to be honest, I have a lot to work on and align on my Path. Thank you so much.

The next portion of experiences and living suddenly became immeasurable.

Thank you for the article. It reminds me of the film ‘Oil’, which has a very illustrative character.

I periodically think it would be interesting to have some sort of interactive board, for example on Miro, where each demon is matched with examples from culture, personality, films. Such an additional alive layer of description.

An excellent idea. Otherwise, it turns out too abstract.