Astaroth and the Archons

Astaroth is one of the demons whose presence is particularly noticeable at the present time; moreover, the very era has made his way of thinking the norm. We live among screens, retellings, summaries, and instant answers, where any question immediately receives a ready-made form, and any experience turns into a comment on it. A person has not yet had time to live through an event, and has already received an explanation of it; has not yet matured to grasp meaning, and already has seen an “analysis” and a “bottom line.” In such an environment, wisdom is easily replaced by mere information, understanding — with mastery of terms, an inner path — with a collection of correct wordings. And therefore the demon of false clarity becomes almost ubiquitous: he merges with social habits, with cultural taste, with the image of “adequacy” that society encourages and approves. One could say that Astaroth’s fetid breath becomes the very atmosphere of modernity — that cold light in which everything seems visible, and precisely for that reason one wants less and less to go further.

He is described as a “great duke,” credited with commanding forty legions, and sometimes — with the duties of hell’s treasurer; at the same time, his “pre-fall” rank is interpreted in different ways, being called either a seraph or a throne, as if the tradition itself hesitates as to what height to assign the source of his influence.

We have already discussed that in different systems Astaroth is described either as a subordinate ruler of knowledge and temptations, or as one of the figures of the supreme level associated with the court of Lucifer. In the “True Grimoire” he appears as Lucifer’s messenger and receives geographical associations, including power over the Americas; in other authors, his role manifests through the temptation toward idleness, when it is easier for a person to accept a ready-made explanation than to endure the hard path to knowledge and the price of understanding. From here also follow indications of traditional means of counteraction, including the intercession of Saint Bartholomew established in the late Christian demonological line and calendar correspondences associating Astaroth with August.

Astaroth is one of the great forces connected with the mind, with logic, and with the process of choice — one of the most widespread distortions of the Apollonian principle of mind. As we already said, the Apollonian principle is the very principle of discernment, the light thanks to which the world becomes understandable at all: as a set of data and relations, the ability to distinguish the true — from the seeming, direction — from walking in circles, a path — from self-soothing.

To a significant extent, from this same first principle archontic rationality also grew: as the world’s constraining logic, as the rigid connectedness of an environment where laws and constants turn out to be not ways of knowing but methods of coercion — and a person gradually begins to feel reality as заранее determined, as a narrow corridor of probabilities in which everything has already been “decided” for him.

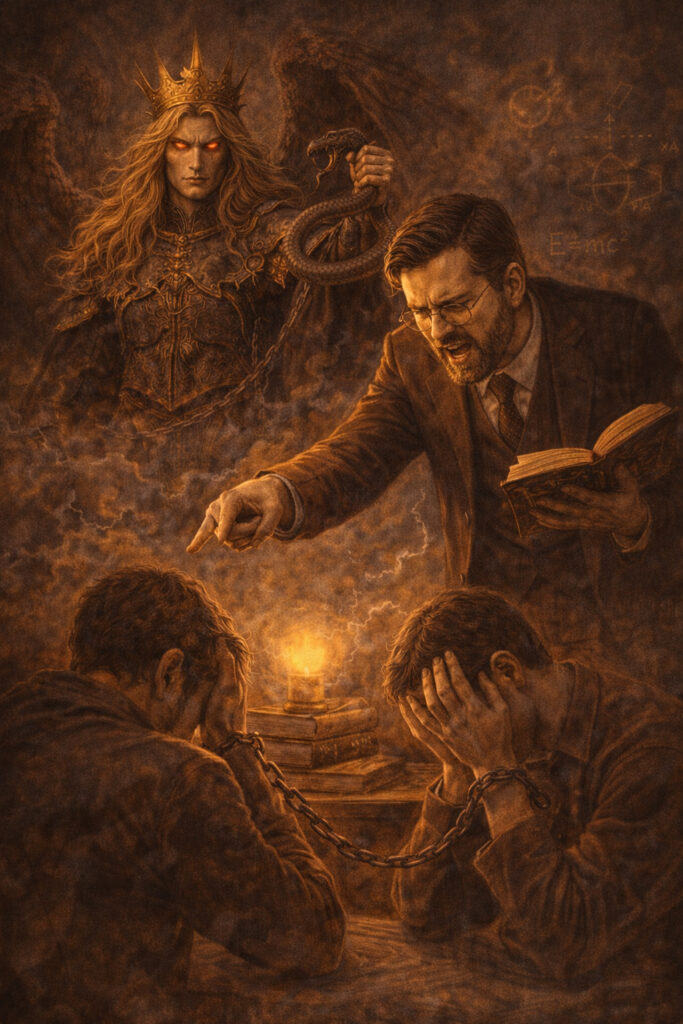

In such an environment, Astaroth can easily find “nourishment” for himself. His classic descriptions mention two important aspects — the beauty of form and the poison of content. He appears as a beautiful but cold angel; next to him is his mount, a snake, a symbol of wisdom that is also a sign of poisoning; and — fetid breath, that is, knowledge in which decay has already begun. This stench in the ritual is felt quite physically, as if the very space of meanings is rotting; and against this background, the demon’s “pleasant voice” becomes an instrument of paralysis of mind, and the stream of arguments turns out to be so dense that the mind simply loses any ability to step back even one step and check where it is actually being led.

We noted that the main hook for activating Astaroth’s matrix in the mind is not thought as such, but the desire to find out. Any demon always feeds on desire, on the energy of motivation. Therefore the introduction of the Duke of false choice begins where the mind is still deciding why it thinks. With healthy Apollonian activity, each thought has its price, its energetic equivalent in time, doubt, observation, changing oneself, re-checking, readiness to live through uncertainties and remain alive inside unresolved questions. Astaroth, however, offers a sense of wisdom without payment, clarity without labor, conclusions without the path to them.

Astaroth is almost always activated when there arises a need to choose the degree of one’s own aliveness: the ability to remain faithful to the voice of one’s heart, to preserve human participation, to choose a direction of development. At such forks, the mind is able to build arguments in favor of any decision, and it is here that the demon replaces the criteria of choice. Instead of the question of inner correspondence, he slips in questions about safety and convenience, about benefit and “adequacy.” And then the choice of self-betrayal is made in such a way that it is almost impossible to doubt it, because the arguments are so coherent, causality so obvious, and the conclusion so resembling maturity. A person feels relief and even pride, because the decision looks impeccable and protected from shame. However, this very relief turns out to be the letting-in of the demon, because although the tension is relieved, growth is forbidden, and the heart is betrayed. And therefore after such a decision, the world seems to become more understandable, but the inner impulse toward development becomes weaker. The ability to love, to risk, to create, to remain faithful gradually weakens, while the solidity and coherence of explanations grow. A person begins to defend his self-betrayal with arguments, turning them into a wall behind which it is convenient not to meet what he would feel if he allowed himself doubt.

This is how his typical replacement arises: a logically grounded conclusion that closes the path to the process of experiencing knowledge, to its emotional sensing. He builds chains of causes and effects, selects facts, speaks the language of “obviousness,” uses the fact that the culture encourages “explanations,” and gradually replaces understanding — with description. The mind turns out to be occupied with talking about a phenomenon or process, while the ability to meet the phenomenon directly weakens. When Astaroth confidently reduces love to chemistry, he deprives experience of the right to be an independent source of knowledge. He turns feelings into an unnecessary or excessive phenomenon, and then thought, even while remaining strict, already serves a dead world.

The hooks he holds onto in the mind are uncompensated feelings of one’s own inferiority, resentment toward the world, secret shame over one’s insecurity, the need to feel superiority over the “naive,” fear of seeming ridiculous, a striving to take revenge on reality with cold clarity.

Astaroth most often affects those who do not know how to open up to their feelings, do not trust them, or fear them, and he tries to compensate for them with logic and “understanding.” When a person fears their own feelings or does not know how to endure them, an inner need develops to keep a distance from experiences. And the most accessible way for this is to turn an experience into an object, give it a name, classify it, break it down into causes, explain its origin, find a “model.” And outwardly it looks like maturity and sobriety, but inwardly it usually just performs the function of anesthesia: the better I have explained, the less I need to live through.

And therefore Astaroth’s trap is not “logic” itself, but the replacement of contact with life — by contact with explanations. A person begins to live as if meaning has already been extracted, and all that remains is to formulate it correctly. In such a state, the mind begins to love not wisdom, not gnosis, but victory, which the “correct explanation” supposedly gives it, because Astaroth’s matrix turns knowing — into a way of self-assertion. This also explains the paralyzing effect of his presence in rituals: the mind encounters “ideal argumentation,” and within it arises a desire to capitulate, because capitulation before such impeccable force looks reasonable.

Such a strategy often increases the risk of intrusion by Beelzebub as well, because suppressed feelings do not disappear; they seek an outlet, and “swings” often arise: “I understand everything” is replaced by an outburst of “I don’t give a damn about your logic,” an emotional revolt, a refusal to think and figure things out. And then the two demons divide the mind in turns: one freezes feelings with explanations, the other complements this freezing with a murky emotional wave.

Astaroth most often enters the mind as one who feeds a sense of one’s own importance. At first, this looks like help, support in a world where there is too much uncertainty, too many inner oscillations, too much pain from one’s own mistakes and others’ unpredictability. He slips the mind a taste for thoughts as a refuge.

When the mind wants support, wants a clear light in which objects stand in their places, Astaroth brings the pleasure of explanation. A person utters a successful formula, finds the “correct” causality, hears a clever interpretation — and inside a pleasant feeling spreads: now it is clear. This feeling is at first gentle, innocent; it seems like a sign of maturity, a way to stop suffering from the chaos of impressions and dangling in storms of emotions.

Further, the demon translates the need for understanding — into the need for completion. A person no longer seeks knowledge as a path; he seeks that final point, the “discharge,” that will remove tension. Thus Astaroth fosters the habit of “hiding in understanding”: when anxiety rises inside, when reality demands effort, when a choice is ahead, the mind reaches for an explanation like for a painkiller. Understanding (or its illusion) begins to perform a protective function; however, at the same time, unnoticed, thought turns into a way not to live.

The next step consists in going beyond experiences: instead of observing phenomena, a person begins to reason about phenomena. Instead of hearing feelings, he reasons about “what feelings are.” Instead of going through experience, he reasons about “whether experience can be trusted.” Such an approach looks philosophical, and therefore seems worthy, but in fact it removes the mind from direct contact with reality and places it into an endless cycle of definitions, where it is easy to preserve a sense of intellectual superiority.

At the next stage, Astaroth creates endless streams of justifications and arguments; they go one after another, coherent, beautiful, outwardly impeccable. And there are so many of them that the mind simply does not manage to stop and check where in this chain the substitution is hidden. Thus he forms a dependence on an authoritative conclusion: the mind increasingly begins to value not faithfulness (since direct experience, immediate experiences that could check authenticity, becomes less and less), but persuasiveness — no longer depth, but faultless coherence.

And at this stage, a gradual cooling of feelings develops. Astaroth does not destroy the emotional sphere instantly; he does not attack it until he gains full power over the mind. In the early stages, he gradually suggests an idea of its imperfection, inferiority. He gradually makes it secondary, then “dubious,” then interfering. He teaches the mind to look at experience only as raw material for analysis, as an object that should be taken apart and explained, but to which it is better not to come too close. A special pleasure arises in observing one’s own pain from outside, as if it belongs to someone else. And this, of course, gives a temporary feeling of freedom from suffering. Then gradually, inner participation weakens; closeness begins to seem like “chemistry,” love — a set of reactions, fidelity — a social construct. And then Astaroth becomes entrenched especially firmly, because his impeccable logic begins to justify any betrayal as a reasonable (or even inevitable) choice. This is his power over choice: he presents retreat — as necessity, when the possibility of any other step seems like infantile fantasy. The inner voice that would speak of love, fidelity, dignity, maturation is branded as “simple biochemistry” or “projection.” After that, inner choice ceases to be an act of freedom and becomes a method of self-defense, where the mind proves to itself that it had no other way out. Astaroth feeds precisely on the energy when the mind refuses life and calls it — wisdom.

Over time his presence becomes an inner commentator. A person opens a book, listens to a lecture, looks at someone else’s fate, experiences their own failure — and immediately inside a stream of explanations rises. These explanations can be smart, well-read, correct in details, but their defect shows in the result: after them the impulse to act disappears, the ability to love and to compassion decreases. Life turns into merely a topic for reasoning; the отказ from participation in life grows; it seems that it is enough that “I understand, therefore I control.”

In a world where “competence” and “analyticity” are valued so highly, a person afflicted by Astaroth often receives reinforcement. People listen to him, believe him, quote him, consider him sober and prudent. He gains status, which, however, becomes the demon’s second hook, because now to step back from one’s icy clarity means to lose face. Therefore he begins to guard his own scheme of the world as property. He argues, proves, mocks the “naive,” gets irritated by living ambiguity, despises what does not fit into linear causality. Thus Astaroth turns the desire to know — into the desire to rule over what is considered knowledge.

The modern digital environment amplifies this process many times over. It supplies endless “ready-made conclusions,” retellings, theses, explainers. A person gets closure to a question faster than the experience that could truly resolve that question has time to ripen. Streams of information come in a dense flow, in which satisfactions flare: now it is clear. As a result, a style of existence is born where a person lives inside other people’s conclusions, collects them like a collection, builds a base of their personality on them, however real inner development almost does not happen. But Astaroth under these conditions receives a mass feeding field: worship of clarity, a cult of arguments, habits of replacing the experience of reality — by its description.

Gradually an inner censor grows in the mind, subordinate to the demonic matrix. This censor discards everything that requires time, emotions, and uncertainty. It demands proof where faith is needed, demands schemes where intuition is needed, demands guarantees where risk is necessary. The mind begins to fear a living step, because a living step always carries the possibility of error. And Astaroth offers “infallibility” in the form of ideal reasoning — and of course his victim chooses reasoning, because it is always safer.

This often happens in love, when a person feels that living presence next to another requires adulthood, responsibility, patience, the ability to hear and change oneself. Astaroth slips him a set of explanations in which betrayal becomes rational: “we are incompatible,” “love is chemistry,” “passion passes,” “we must think about the future,” “I choose myself.” And although these ideas may be partially true, they translate life from a boiling state — into a rational plane, and then only cold emptiness remains, which must again be explained — and thus the demon gets his second circle of power.

Another consequence of possession by Astaroth is a carefully hidden deep feeling of inner loneliness, which is born not from the absence of people nearby, but from the absence of participation. When the world becomes fully explainable, it ceases to be an encounter. And then people turn into sets of motivations, love — into biochemistry, meaning — into usefulness, faith — into a psychological crutch. A person may look strong and collected, but inside him a cold emptiness grows. This emptiness is Astaroth’s final seal: the mind navigates descriptions better and better and recognizes life worse and worse.

Words become more numerous; inner movement becomes less. Explanations come instantly, and the more the mind is proud of its “sobriety,” the easier it is for Astaroth to hold it in the cage of final conclusions, where understanding has already been obtained, so there seems to be no need to grow.

Thus, Astaroth’s matrix, like that of many other demons of the kingdom of ignorance, grows out of a distortion of the Apollonian principle. He is that shadow that grows where discernment becomes an end in itself. Apollo as a principle creates enumeration for the sake of life, for the sake of a true step, for the sake of responsibility. Astaroth, however, builds logic for the sake of dissection, for the sake of power over the picture of the world, for the sake of abolishing the troubling mystery as a condition of growth. Therefore his wisdom is cold: it abolishes participation; it demands that experience submit to understandable schemes. If in the stream of Dionysus life is experienced as a stream of immediate presence, then under Astaroth’s power presence is replaced by commentary — and this commentary is declared more real than what is being commented on.

Therefore it is clear that Astaroth is often described as one of the manifestations or faces of the Great serpent — Nahash. And in this he draws close to another group of forces, also grown from false clarity — to the Archons. They relate to the world as a substrate and as a field for the distribution of possibilities.

We already said that while in the mode of creativity and crossing the Threshold the mind is vulnerable to gatekeepers, in the “stationary” mode, where a person uses the resources of reality, he ends up in the field of heimarmene and archontic governance; in this, demonic influence manifests as the enslavement of desires, and archontic influence — in the paralysis of will.

Accordingly, while Astaroth gives the mind a striving for false clarity, the Archons create a world in which false clarity becomes the базовая currency of existence. The similarity of their influence is felt as “closing the horizon”: in the mind the space of living potentiality narrows, the sense grows that there is nothing more to seek. The Archons form an environment where a person is constantly imposed standard trajectories and заранее “prescribed” roles, while Astaroth whispers that a person should choose these trajectories as if by his own wisdom. As a result, external givenness turns into an inner virtue, and a person begins to defend his own unfreedom as a sign of maturity.

Thus, archontic influence forms an external inevitability: rules, procedures, constants, standard routes, algorithmic norms, in which reality is built as a mechanism requiring servicing. Astaroth, however, forms an internal state of inevitability: explanations that present this mechanism as “the only reasonable” one, and explanations that заранее justify отказ from living experience and from the long path to wisdom. And while the Archons keep the mind in a given trajectory, Astaroth cultivates pleasure from the very idea of given-ness, which looks like maturity and common sense.

Astaroth gives a sense of control through knowledge of terms and glosses. He replaces maturity with knowledge of definitions. And the archontic side builds up the “mechanization” of life, technocratization, the fading of creative impulses, the redistribution of human energy in favor of the Rulers.

It is easy to notice that, despite the similarity of influence, competition for energy hardly arises: the Archons direct to their “wards” energy that is tied to prolonged vital activity: habits, routines, dependence on systems, involvement in an infrastructure where will slowly thins and begins to perceive powerlessness as the norm. Astaroth, however, feeds on what is connected with the inner justification of this state, when a person explains to himself his own exhaustion as “objective reality,” his own cooling — as “sobriety,” his own spiritual blindness — as “critical thinking.” He gives a person a sense of intellectual victory precisely at the moment of inner defeat, when the psychocosmos is unbalanced and “bleeding.” The energy supplied to the Archons is vital force that could have been spent on fully living through, extracting, and sealing experience; and Astaroth’s “food” is the unrealized desire to live, the energy of strangled emotions and sensual impulses, replaced with “cold” reason. In this alliance the Archons receive a manageable performer, and Astaroth receives a consumer of explanations who voluntarily accepts explanation more valuable than self-development.

The Archons intensify the need for predictability, because predictability is important for the stability of the mechanical world; Astaroth, in turn, offers predictability in the form of final conclusions and meanings set “once and for all.” The Archons turn life — into a procedure, a technological process, and Astaroth passes this procedurality off — as wisdom. It is in this sense that Astaroth’s “fetid breath” is the smell of knowledge that has ceased to lead, that no longer nourishes life, but only preserves corpses.

Contact with a bearer of Astaroth leaves a feeling of a closed door: it is evident that although clarity is present in him, the movement of life is not. And the sharper his thoughts become, the poorer life. Such a person almost always has developed contempt for the “naive” and a strange pride in his own coldness.

And if Astaroth holds one back from living through life, the Archons do not even allow it to begin: they extinguish the very inner fire of mind, and will under their influence prefers safe repetition, and the world seems “too solid” for a new impulse to arise in it.

Opposition to Astaroth is always connected with returning a worthy price to knowledge. It is necessary to return a sense of process to knowing, the function of a path on which conclusions are tested by life, and understanding increases the ability to love, choose, respond, endure — not only increases the ability to argue. The Apollonian principle should be returned to its rightful place, when discernment serves reality and the soul; and then Astaroth loses ground, because his food is the illusion of already achieved wisdom.

Thank you.

Thank you for the article!

In general, based on my observations, only those who have gone through a “touch” with the darkness can adequately explain and convey something clearly.

Those who received information from above and have no experience of darkness seem incapable of doing so. The information coming from them resembles a flow of high-sounding nonsense.

But only recently did I understand why. And it seems that only the “matrices” of Astaroth help structure, organize, and properly present what has come.

I had enough communication with one of them, but you have called almost all the known ones.

I read your books,

but haven’t you asked “them”,

“why did the angels fall”?

And why “could not they help but fall”?

I have my own explanation. But still, I would very much like to hear “their” version.

If we are talking specifically about “fallen angels”, then the term better applies to the Grigori rather than demons, since demons did not “fall” in time; there was no time when they were genuinely “angels”, although their nature is indeed the same as that of angels – servile vortices.